|

| HOME - - Land Introduction - Armley Mill - George Stell, Wool Comber - Benjamin Law, Inventor of Shoddy - Robert Walker, Slubber Overlooker - - Land connection pages |

|

The Lands, Laws, Stells, Sykes, and Walkers and the Weaving

Industry

In addition to the fact that they were related by marriage, the Lands, Laws, Stell, Sykes, and Walkers had another common "thread". They lived in woolen manufacturing centers of the West Riding of Yorkshire and at least one member of each family worked in some capacity in the weaving industry.

Weaving With Wool All wool is not created or woven equally. Various kinds of sheep are raised for different types and lengths of fibers. These different types of fibers are woven into different types of cloth. Worsted is made from smooth compactly spun yarn. Long fibered wool is combed and spun using an average to hard twist in the spinning. The fabric is napless and tightly woven. Worsted is used for clothing, like suits. Woolen is made from fuzzy, loosely spun yarn. Short fibered yarn is carded and spun using an easy twist in the spinning. The fabric is nappy and bulky. Woolen is used for heavy clothing and blankets. Shoddy is made from a mixture of recycled woolen rags and virgin wool and is treated like woolen. Shoddy was developed in Batley, Yorshire by Benjamin Law circa 1813.

|

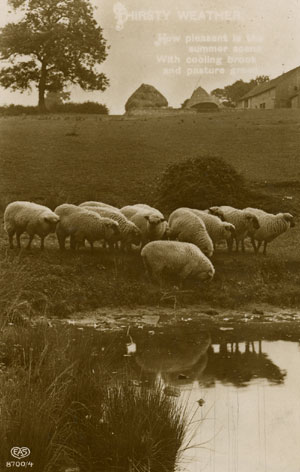

| The Sheep and Shearing |

|

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck |

|

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck |

| Woolen and worsted are both processed on hand looms from fleece to cloth in roughly the same way. The farmer often washed (or half washed) the sheep before shearing to remove the fatty secretions that protect the sheep but which must be removed to process the wool. At other times the fleece is washed after shearing. |

|

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck

|

|

Sheep shearing Posted Burton on Trent 1905 |

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck

|

|

Sheep shearing Posted Skeoness Linc. 1909 |

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck

|

|

Sorting

After the fleece is shorn from the sheep it is sorted by type and length of fiber. | |

|

Sorting Wool After Cleaning and Washing Lawrence Mass. USA, date unknown |

| Slide collection of Maggie Land Blanck After the wool is soted it is"combed" if it is worsted and "carded" if it is woolen before being spun into yarn. See Combing and Carding below.

| |

| Carding - Woolen | |

|

|

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck Carding Wool, Old Fort House, Plymouth, Mass. I have not been able to find images of wool carding from England. This reenactment of the old method of carding was the same for both the United States and England at the time. | |

| Combing - Worsted | |

|

|

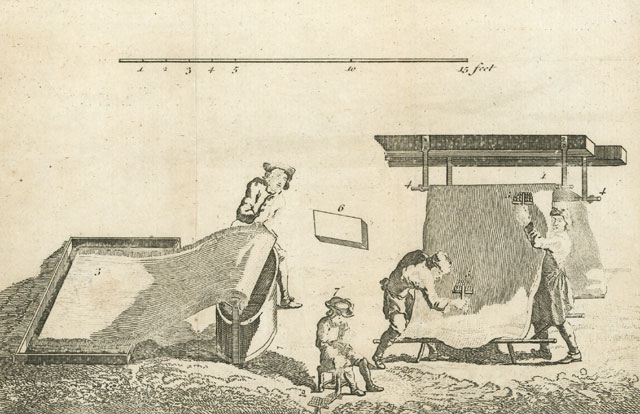

| Print collection of Maggie Land Blanck This image entitled "The Combing Work" shows both the washing and combing. In August 2009 Heather Seddon wrote in regards to item #6: I think it is for wringing out the wet fleece.In November 2009 Jared Fleury suggested that item #6 may be a felter and referred me to Kumanovo In June 2011 Tony Powell asked in reference to item #6: "Could it be that the fleece was actually wrung out by hooking the two ends, one fixed and the other turned using the handle?" | |

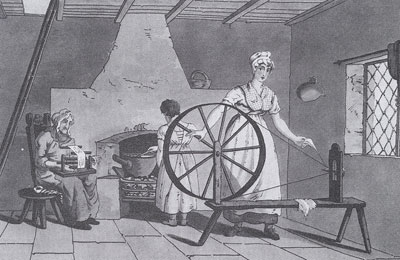

| Spinning | |

| Spinning on a great wheel. Image from The Costume of Yorkshire by George Walker, 1814 To see this picture and others from this series in color, go to Life in Yorkshire, now or at the bottom of the page. The yarn is wound onto bobbins, where it is stored until ready for weaving. |

| Weaving | |

| |

|

Warp threads are tied onto the loom. They are passed through a reed, which

keeps them in order and serves as a beater after the weft or cross thread are passed.

After the warp threads are threaded through the reed, they are passed through hettles,

which allows the weaver to raise and lower different warp threads.

Weft threads are "shot" or "thrown" across the warp threads.

The cloth is "beaten", (that is packed towards the already completed part of the cloth),

after each shot of weft thread. Alternating weft threads are raised and lowered after

each shot of weft thread. When the cloth is finished it is removed from the loom.

| |

| Washing of finished cloth | |

|

|

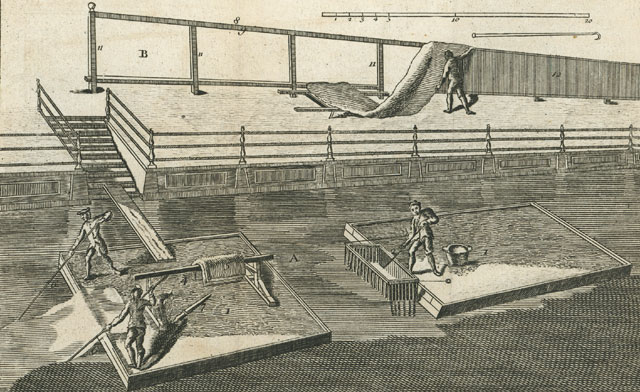

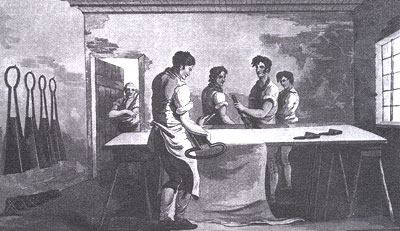

| Print collection of Maggie Land Blanck This images shows "the washing of the wool and hanging up of Woolen Cloth". In the old process woolen was then "fulled" (a process of shrinking the cloth by applying, dampness, heat and pressure to the cloth). Depending on the part of England where they lived three surnames developed for people who completed this part of the operation: Walker in the north and mid lands, Fuller in the south-east and Tucker in the south-west. Walker developed because the men who fulled the cloth did so in part by walking on it. After the cloth was fulled it was strung on tenters in the open air to dry and be shaped. | |

|

| Photo of the tenterhooks at Otterburn Mill in Northumberland, courtesy of Lesley Abernethy December 2011 |

| |

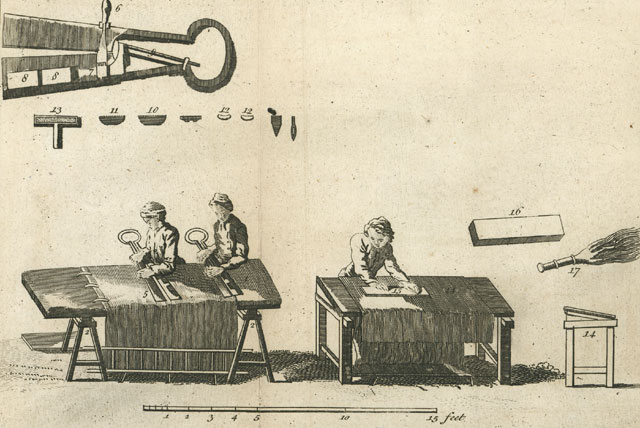

| Print collection of Maggie Land Blanck Next the cloth was "dressed" and "finished". The dressing involved drawing out any loose fibers from the cloth with teasles which also raised the nap. The men on the right in the above images (called "the working of wool") are "dressing" the cloth. The combs in their hands have teasle attached to them. See teasle below.

|

| |

| Print collection of Maggie Land Blanck Next the nap was cut with shears as closely as possible the surface of the cloth so that the surface appeared smooth. The image of "the Shear -mans work" shows the shears in the upper left and the shearmen below. Cloth drawers (or finishers) inspected the cloth and used a needle to made any necessary repairs to small holes or blemishes in the fabric. Finally the clothe was pressed and packed for market. Adding color can take place at any one of three times:

| |

| |

| Print collection of Maggie Land Blanck, October 2011, donated to

Tucker Hall, Exeter, UK Draperie, Tonture et Apprets des Drapes, date unknown "Tuckers Hall is the home of the Incorporation of Weavers, Fullers & Shearmen and both the Hall and the incorporation have a remarkable story with a glorious and continuous history since 1471." |

The Clothier A "clothier" could be:

The majority of clothiers were not large manufacturers. They also did a little farming on the side, mainly raising vegetables and crops that did not require a lot of attention. Attached to the clothier's cottage was a piece of land that ranged in sized for one to fifteen acres. The clothier kept some animals; poultry, pigs, a cow or two, a horse and/ or an ass. As mentioned, carding and spinning were usually done by the small clothier's wife and children. Large clothiers had spinning done outside the shop. The small clothier, assisted by his son or apprentice, warped the loom and did the weaving. After the cloth was woven it was taken to the fulling mill. When the cloth was dry, the clothier put his cloth on his horse or donkey, or carried the cloth on his own back and brought the cloth to the market towns, where he sold it. There was still work to be done on the cloth after the fulling, but the clothier sold the cloth in the "rough" and left the finishing to the cloth finisher. The major markets for the cloth were in Leeds and Halifax. |

|

Clothmakers on their way to the market. From The Costume of Yorkshire by George Walker, 1814.

To see this picture and others from this series in color, go to Life in Yorkshire, now or at the bottom of the page.

|

| Cloth finishers were also know as "dressers or croppers". The raised the nap of the cloth with teasel and then cut the nap to a uniform surface using the shears that weighed up to 40 pounds and were four feet long (pictured below hanging on the wall to the left). The croppers were well paid and resisted the attempts of their employers to introduce shearing frames at the beginning of the 19th century (See Luddites below) |

|

Cloth finishers From The Costume of Yorkshire by George Walker, 1814. To see this picture and others from this series in color, go to Life in Yorkshire, now or at the bottom of the page.

|

|

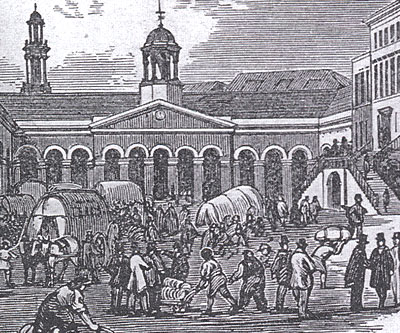

The Cloth Markets and Cloth Halls The woollen industry was centered around Leeds, Wakefield and Halifax. The major cloth markets were in Leeds and Halifax. Daniel Defoe toured England and Wales in 1724-26 and included in his diary a description of the cloth market in Leeds. "The street is a large, broad, fair and well built street, beginning as I have said at the bridge and ascending gently to the North. |

|

A Leeds cloth hall |

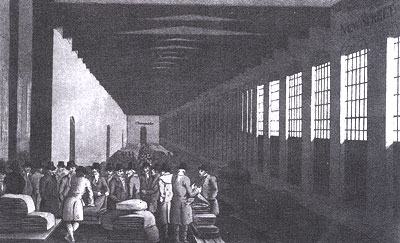

| Interior of the Colored Cloth Hall from The Costume of Yorkshire

by George Walker, 1814

To see this picture and others from this series in color, go to Life in Yorkshire, now or at the bottom of the page.

|

|

Highlights from the History of the Woolen Industry in Yorkshire Weaving with wool has a long history in England.

For centuries entrepreneurs bought raw fleece and transported it to rural farm families to be spun and woven. In the winter when there was not much work to be done on the farm, the farmer's wife and children carded and spun the yarn and the farmer wove it into cloth. The farmer was paid by the piece. The finished produce was shipped from the ports of Bristol and London to Europe. By the middle of the 1700s many families in the West Riding were involved in making cloth, either woolen or worsted. By 1773 it is estimated that 3,000 cloths a week were sold in Bradford alone. Until 1851, 85% of the population of England, lived in communities of fewer than 5,000. Most of the rural and semi rural population was engaged either in the domestic manufacture of textiles or they supplied agricultural, mining, or building needs to the rest of the rural community. In good weather combing and spinning would become social events when young women and children brought their spinning wheels out into the streets and open places and gossiped while going about their work. |

|

| |

|

|

| Photo collection of Magie Land Blanck

Old Weavers Houses at Bethnal Green circa 1897. In pre-industrial Yorkshire the weaver's lofts were on the second floor and had large windows to let in the light. | |

|

| |

|

|

| Photo collection of Magie Land Blanck

Heptonstall Weavers Cottages', Yorkshire 1950 | |

|

The Industrial Revolution The Industrial Revolution of the 18th and early 19th century was a British phenomenon. It began in the cotton and iron industry. Until that time, the woolen and worsted industries had been much more important in volume and income than the cotton industry. Cottons were mostly imported from India and were considered cheap fabric. With the advent of the cotton gin (to de-seed cotton more cheaply) and the spinning jenny (to spin more quickly) cotton started to become an important industry in England and in the United States. By 1815 cotton exports from England exceeded woolen exports by three times. The technical innovations in cotton spinning and weaving combined with the fact that cotton was basically a new industry and consequently unrestrained by tradition, allowed the rapid introduction of power machinery into the cotton industry. Woolen and worsted manufacturing lagged behind industrialization for at least two reasons:

Before 1760 England had been a sparsely populated agricultural country. Its population in the middle ages was between 2 and 3 million people. By the early 18th century it had risen to about 5.5 to 6 million . Around the middle of the 18th century the population started to grow more rapidly and continued to grow through the 19th and 20th centuries. The first census in England take in 1801, showed the population at 9 million, by 1831 it was up to 14 million and by the end of the century it was at 32.5 million. There is much debate as to what caused this tremendous increase in population. But it boils down to:

As the population grew people who had been born in rural areas began to shift towards the towns in the mid-land and the north of England where jobs could be found in the new and quickly growing industries. Towns and cities that had been sparsely populated started to grow very rapidly. Leeds, for example, went from a population of 83,746 in 1821 to a population of 207,165 in 1861. This increase in population is partly responsible for allowing the industrial revolution to take place, as it initially provided a large work force. Ultimately, as more and more industries became mechanized, however, there was less work in certain industries. Some of the biggest changes occurred in the textile industry.

In the eighteenth century a revolution in the textile industry was brought about by a series of inventions; firstly that of the "fly shuttle," by John Kay of Bury in 1733, which doubled the productive power of the weaver; secondly the 'spinning jenny," invented by James Hargreaves of Stanhill, Blackburn between 1764 and 1767, by which sixteen or more threads could be spun at once; thirdly, the "water frame," invented or improved by Richard Arkwright in 1769; fourthly the "spinning mule," a combination of the methods of Arkwright and Hargreaves, invented by Samuel Crompton in 1779; and lastly the "power loom" invented by Edmund Cartwright between 1785 and 1792. He also invented two distinct forms of wool-combing machines. These inventions, with the exception of the last two, were first applied to cotton, and not until a generation later to wool.While the effects of Industrial Revolution were slower to change HOW things were done in the woolen and worsted industry, it did have an almost immediate effect on WHERE things were done. Instead of being spread throughout the entire country, woolen and worsted manufacture became concentrated in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Yorkshire forged ahead in the woolen and worsted manufacturing industry for a variety of reasons:

This combination of supply and the cheapness enabled the area to lead the market at home and aboard. Dewsbury and Batley were particularly known for their cheap woolens. This increased production of woolen goods preceded the advent of the factories as the actual place where the weaving of woolens and worsted was carried out. In other words, much of the work was still done at home. As late as 1856 only about one-half of those employed in the woolen industry in the West Riding were employed in factories. In the West Riding in the mid 1800's it was common for a group of woolen "clothiers" to get together, send the wool to a mill to be cleaned, carded, and spun. The prepared wool was then sent to the weaver's home to be woven. After it was woven on a hand loom at home it was sent back to the mill to be fulled. It was then sold to a merchant who would dye and finish it to be ready for use. Fulling the fabric had been carried out in water powered mills for centuries. Carding and spinning machines were new inventions that greatly increased the productivity of that part of the process.

The adoption of the power loom in woolen manufacturing was very slow. In 1836, Yorkshire had only 688 power looms for woolen weaving. There were four times as many looms for the weaving of worsted. The entire cotton industry had been using power looms almost from it's inception is England. One of the reasons it was hard to adapt power looms to woolens was the loose spin on the yarn making it liable to break more easily. The weaver had to retie the threads by hand and the power loom could not work any faster than a handloom weaver if the threads broke often. Initially, it was felt that the labor saving aspects of a power loom for woolens was not worth the expense of the new machinery. However, because the area grew so rapidly in woolen and worsted manufacturing it eventually became the place in which to invest in the new machinery when it was finally make compatible with wool weaving. Although the industrialization of the woolen industry came more slowly than in the cotton industry, and even more slowly than the worsted industry, it did eventually come. When industrialization arrived in Yorkshire there was an additional advantage. Yorkshire had and abundance of both coal and water power which were needed to run the new factories. The immediate effect of the Industrial Revelation on hand loom weavers were beneficial. Because of the increase output of yarn from the introduction of new spinning machines the weaver had more raw material and was in greater demand to turn it into a finished produce. He could therefore demand a higher wage. Wages eventually fell because:

By the 1840s the handloom weaver and the power loom weaver were in competition in the woolen industry. Until that time the two co-existed and the supply of handloom weavers was always in excess of the demand for their labor. "only in the 1840's in the woolen, industries did the power looms in the factories competed fully and directly with handlooms. Until that time the two existed side by side, with the handloom weaver reduced to being an auxiliary of the factory, but not yet driven out of existence by competition. His role was to take up the slack in bust times, and to bear the first brunt of recession. He also acted as a check on the wages of power loom weavers, most of whom were women. The plight of the weavers was a vivid illustration of how helpless a section of laboring men could be when caught between the relics of the domestic system and the full force of competitive industrial capitalism."The occupations of some of the Land/Law ancestors (as indicated in the censuses) show these changes. By 1841, if not before, William Law was working in the woollen manufacturing trade, first as a spinner in 1841 and by 1851 as a "handloom weaver". In 1861 William Law was a "wool hand loom weaver" and his daughter, Mary Ann was a " wool power loom weaver". By 1891 Ann Sykes Nussey isn't making any differentiation, she is just a "woolen weaver". Given the date, I assume she is working on a power loom. In 1866 there were 1,000 hand loom weavers in the Heckmondwike district, in 1884 there were 640. Hand loom weaving held its own and survived longer in the carpet trade than in any other branch of the textile industry.

Wool Combing, Before and During the Industrial Revolution George Stell, born in Keighley in 1752, was a woolcomber from a family of woolcombers. See George Stell. Wool "combing" is connected to the worsted trade. Before combing began the wool was washed, oiled and laid out on a bench in "handfuls". Handcombing is a three step process: feeding, combing and drawing off.

In the 18th century the handcombers were an important element in the worsted trade. It appears to have been an occupation that was handed down from father to son and the woolcombers unions were strong. They were well paid and prosperous. In 1747 a handcomber eared from 12 to twenty-one shilling a week, and were among the best paid workers in the trade. With the advent of the industrial revolution inventors were contiuously trying to come up with a combing machine. Various machines were introduced but none of them were truly successful until about the middle of the 1800s. By the 1840s woolcombing machines had seriously threatened the handcombers existence. However by 1825 the decay of handcombing was well under way. The introduction of wool combing machinery insured the extinction of the trade. In 1825 there was a prolonged strike where twenty thousand wool combers and weavers were out of work for 22 weeks. In the end they were compelled to return to work without having met their objective of an increase in wages. In Bradford in July 1825 the woolcomber's union struck for higher wages. They contended that they were working long hours for insufficient pay. It was stated that the best workers labored from 4 A.M. to 10 P.M. for only 14 to 16 shilling a week. Opponents of the wage increase countered that the wool combing shops did not open until 5 A.M. and were closed at 8 P.M. (A mere 15 hour day!) "and that even these short hour of labour were lessened by the fact that about an hour elapsed each day before the men commenced work and an hour a day was allowed for meals."The strike went on for months. It was finally settled in the favor of the employers in October. The handcombers were brought back at the same wages and hours that had brought them to strike.

|

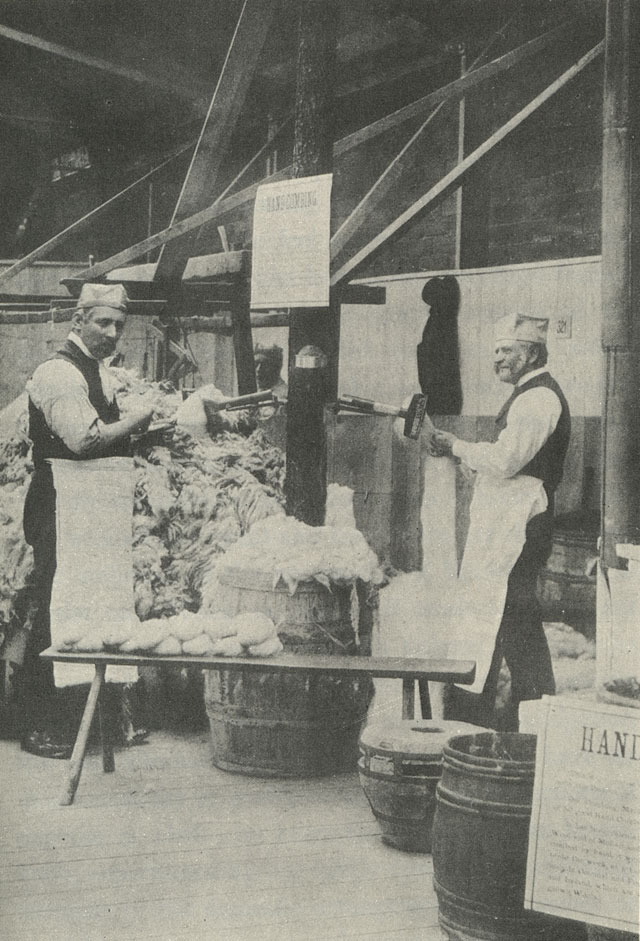

|

| Illustrated History from Hipperholme to Tong

James Parker, 1904

|

|

Unfortunately the quality of this image is not the best. However, several things can be

observed in this pre Industrial Revolution combing workshop including the large bales and

barrels of raw wool. Almost dead center in the picture a small table contains

rolls

of the combed wool, called tops. Beneath the table of tops is a charcoal blazier.

Additional combs are hanging off the

brazier to become warmed.

The men are wearing aprons

and hats to protect themselves from the debris that falls from the fleece.

In November 2011 Mary Bolton wrote in reference to the heating of the combs: "I think it might be to soften the lanolin which is on the wool and would be waxy and viscous at room temperature." |

|

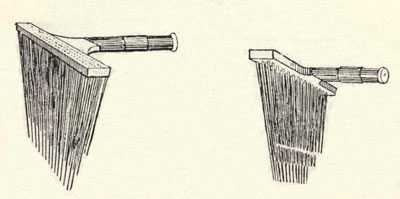

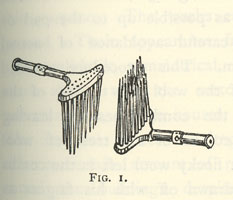

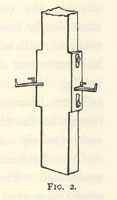

Hand combs |

Illustrated History from Hipperholme to Tong

James Parker, 1904

A transcription of a letter from Sir Henry Mitchell to the government in 1884 was included in

Yorkshire, Scenes, Lore and Legends, by M. Tait, written in 1888.

Sir Michell says that in 1839:"wool was entirely combed by hand, and the work was done to a large extent in the cottages of the workpeople. As charcoal was largely used for heating the combs, the occupation was very detrimental to health and this, combined with bad sanitary conditions, caused the average mortality to be greatly in excess of the present time." | |

|

|

| The History of Wool and Wool Combing James Burnely, 1889 | |

| Another set of wool combs and the post hook for hanging the "pad" comb.

| |

|

| The History of Wool and Wool Combing James Burnely, 1889 |

| Hand woolcombers

|

| |

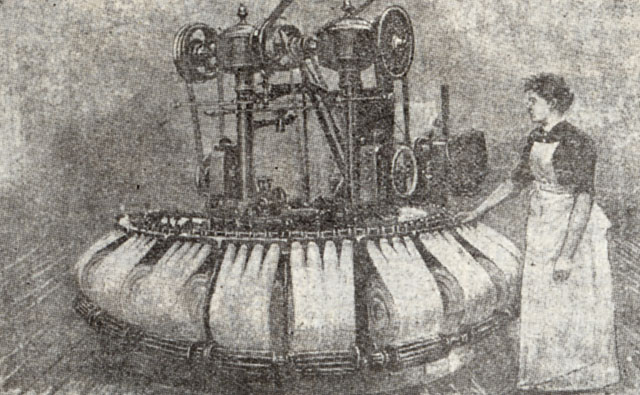

| Illustrated History from Hipperholme to Tong

James Parker, 1904

| |

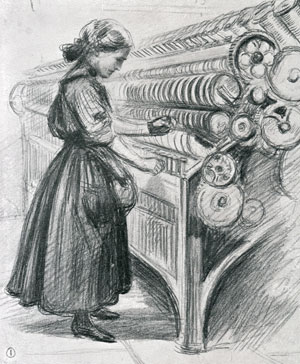

| In this picture of the NOBLE COMB of 1904 one can observe how

the Industrial Revolution both speeded up the process and reduced the number of "combers"

needed. One young woman

had replaced 100 combers of old.

| |

|

|

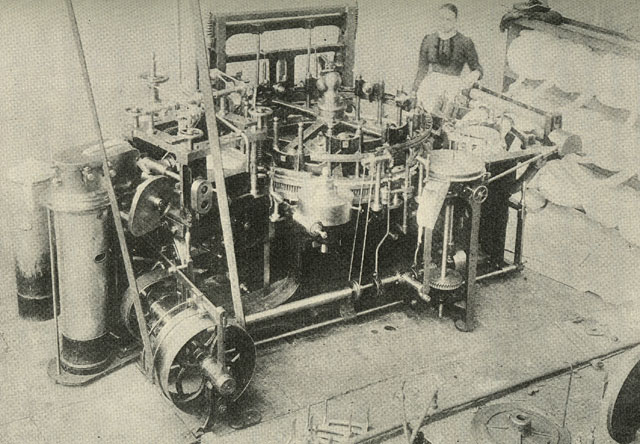

| The History of Wool and Wool Combing James Burnely, 1889 | |

| General View of The Square Motion Woolcombing Machine

| |

|

Woolcomber's Health Extract from Volume II of "The Civil, Ecclesiastical, Literary, Commercial and Miscellaneous History of Leeds, Bradford, Wakefield, Dewsbury, Otley and the District within Ten Miles of Leeds" by Edward Parsons (1834) which examines the effect of industrial working conditions on public health. "Woolcombers work in apartments which, from the fire employed to heat the combs, are kept at the temperature of about 80°. The fires are made of charcoal. A light dust arises from the wool. The lungs suffer so much, that many persons cannot pursue the employ. The men, however, generally appear quite healthy." | |

|

St Blaise, patron saint of woolcombers St Blaise (Blaize) was the patron saint of woolcombers. Processions of woolcombers were held in the West Riding of Yourshire on the Feast of St Blaise, February 3rd. The following article on St Blaise included a description of the St Blaise festival in Bradford in 1825.

CELEBRATION OF BISHOP BLASEA St Blaise procession was held in Wakefield in 1829. See Life in Yorkshire for an image of a St Blaize procession. Slivers were overlapping untwisted strands of combed wool. | |

Spinning, Before and During the Industrial Revolution

|

|

|

| Print collection Maggie Land Blanck Publication unknown 1888. This image represents distaff spinning where long fibers such as wool or linen could be spun from a bundle of fibers attached to a long staff. Using a drop spindle the spinner could stand or walk while spinning. In February 2009 Lee Hutchings an Architectural Historian wrote to point out that the three women represented "three Fates of Greek mythology who controlled the threads of human life, called" Clothos, Lachesis and Atropos". Clotho spun the thread of life, Lachesis measured it and Atropos cut it, so choosing the manner and time of each persons death. Lee pointed out two web sites. Moirae and fabulous depiction of the three fates from the fantasy Victoria Castle at Castell Coch, South Wales

See also Castell Coch (Red Castle) | |

|

The Bygone Spinning-Girl And The Old-Fashioned Spinning-Wheel A variety of spinning wheels were developed over the years. Some were specific for the type of yarn being spun. The basic principle, however, is the same. |

| Print collection Maggie Land Blanck The Graphic February 1 1913 - "In the City of the Sheep: A Town Founded Upon Wool, Scenes in Bradford, Yorkshire's Great Cloth-Making Centre, Which Supplies the World With Worsted Cloth" | |

|

Bobbing Wheel 1826 |

| Illustrated History from Hipperholme to Tong James Parker, 1904 Part of the industrialization of spinning included the process called slubbing which was introduced around 1786 with a machine called the slubbing billy. Slubbing, a step between carding and spinning, was one of the earliest mechanized processes. The slubbing billy took the carded wool (which was in the form of "slivers') gave it slight twist and made it into a continuous yarn which was wound onto bobbins. Robert Walker born 1809 in Morley was a slubber. See Robert Walker | |

|

|

Scribners magazine, 1878, collection of Maggie Land Blanck Spinning mules.

|

|

"The Modern Spinning girl and Her Wonderful Machine" |

| Print collection Maggie Land Blanck The Graphic February 1 1913 - "In the City of the Sheep: A Town Founded Upon Wool, Scenes in Bradford, Yorkshire's Great Cloth-Making Centre, Which Supplies the World With Worsted Cloth" | |

| The spinning mule at Armley Mills Museum |

|

|

Referring to the numbers in the photo above this is how the mule worked: 1. Large bobbins containing slivers were placed on the rollers behind the spinning frame. 2. The frame which contains 3. the smaller full bobbins of spun yarn moved on 4. wheels and 5. tracks The are two frames that move towards each other. The frame containing the bobbins of spun yarn moved away from the rollers containing the slivers. When the bobbin frames were furthest from the rollers a twist was given to the yarn. As the frames came back to the rollers the newly spun yarn was wound onto the small bobbins on the frame. Since the threads often broke during the spinning process it was necessary to reconnect them. This was done by a piecer who joined the broken threads by hand. Until child labor reform laws restricted young children from working in the mills, piecers were general children whose hands were small and agile enough to reach in and retie the threads. |

Warping and Dressing the Loom, Before and During the Industrial Revolution Before the Industrial Revolution the weaver probably performed the tasks of preparing the yarn for the loom. This involved measuring out the yarn for the warp (or lengthwise threads) and then drawing each thread of the warp though the heddles of the loom.

|

|

|

| Print collection Maggie Land Blanck

The Graphic February 1 1913 - "In the City of the Sheep: A Town Founded Upon Wool,

Scenes in Bradford, Yorkshire's Great Cloth-Making Centre,

Which Supplies the World With Worsted Cloth"

"A Corner of the Warping Shed" 1913 | |

|

Weaving, Before and During the Industrial Revolution

|

|

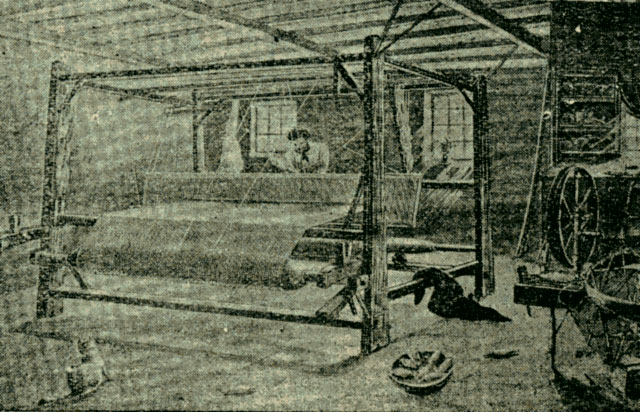

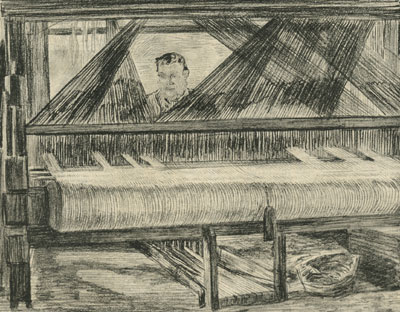

Illustrated History from Hipperholme to Tong

James Parker, 1904

From Sir Henry Mitchell letter on the Worsted Trade in 1884 transcribed in Yorkshire,

Scenes, Lore, and Legends 1888:

"Weaving was also mostly done by hand, and was also carried out in the houses of the operatives. Power looms were then just being introduced, but weaving by hand continued to some extent for about ten years. Now it is almost entirely superseded by power loom.

|

| "Here is shown the interior of an old hand-loom weavers house, at Stanbury, near Haworth; he is sat in the house, and the house "baulks" are filled with old-fashioned pint pots; a bobbin wheel is also in." |

| Illustrated History from Hipperholme to Tong James Parker, 1904 | |

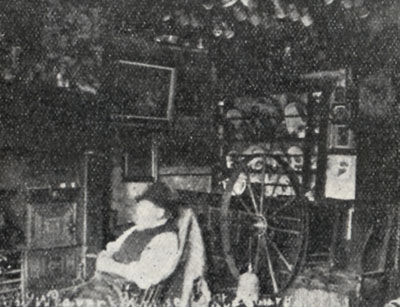

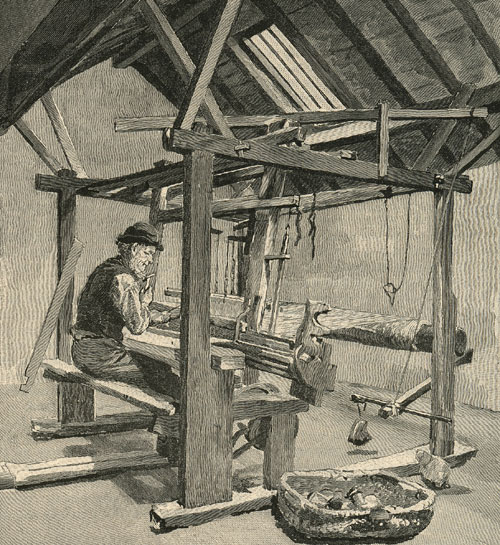

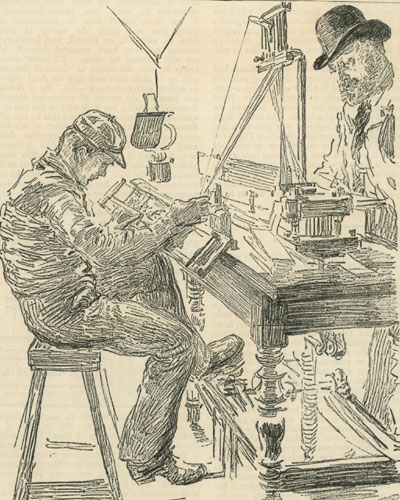

| Painting by Gilbert Wilkinson |

| "The engraving shown below represents the old weaver in his camber weaving cotton pieces. He is eighty years of age, and has a ready sale for his goods, his hand-loom, bobbin wheel and his bed are shown." |

| Illustrated History from Hipperholme to Tong James Parker, 1904 &mdash also postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

Hand Loom Weaver form unknown 1888 publication |

| Print collection Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

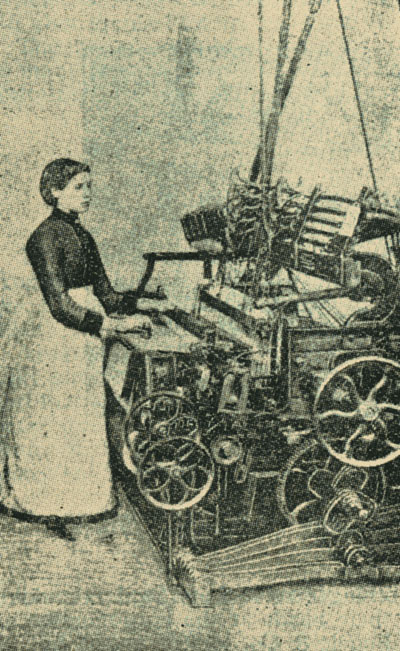

In his letter Mitchell neglected to mention that the power loom weaver was frequently female and young. William Law was listed as a clothier (weaver) at the birth of his daughters between 1840 and 1849. In the 1851 and 1861 censuses he was listed as a hand loom weaver. In the 1861 census his 15 year old daughter, Mary Ann, was listed as a power loom weaver. |

| Illustrated History from Hipperholme to Tong

James Parker, 1904

|

| |

| Yorkshire West Riding By B Hobson, 1921

| |

|

"A Weaver A Work" 1913 |

| Print collection Maggie Land Blanck The Graphic February 1 1913 - "In the City of the Sheep: A Town Founded Upon Wool, Scenes in Bradford, Yorkshire's Great Cloth-Making Centre, Which Supplies the World With Worsted Cloth" | |

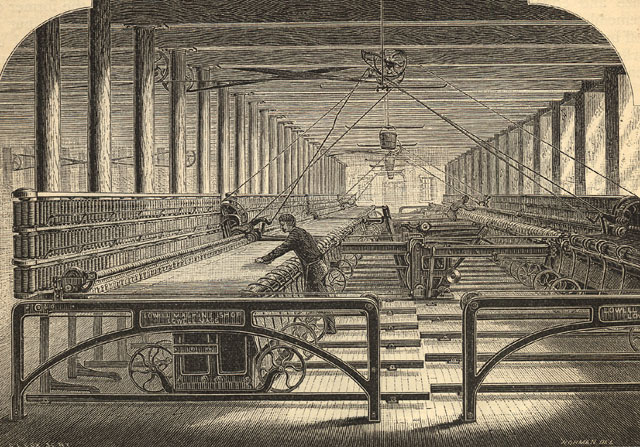

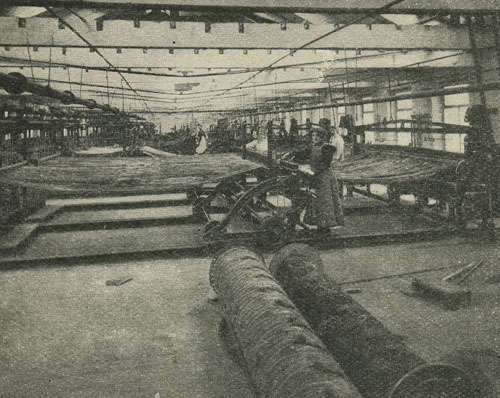

|

| Print collection Maggie Land Blanck INTERIOR OF MARSHALL'S FLAX-MILL While this is a flax mill and not a woolen mill, the look was similar. |

|

The Large Loom |

| The Graphic May 26, 1888

| |

|

Punching Cards for a Jacquard Loom |

| The Graphic May 26, 1888 Preparation For Weaving On A Jacquard Loom The Jacquard loom (named for its inventor) used cards as a means of allowing the weaver to make very complicated patterns. "The first process connected with weaving is to have the design drawn on paper, divided by machine ruling and into squares each square representing one thread in the fabric.A "doyley", made in Ireland which was presented to Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, on the occasion of her Jubilee contained 3,060 warp threads and 4, 012 weft threads. The paper on which the design was drawn was divided into 12,000,000 squares and took the draftsman seven months to complete. The design used 20,000 cards containing 10.000,000 punched holes which took six months to complete. The total time tying knots and preparing the loom for weaving took seven months. | |

|

Shuttle |

| Ernest Lippert was an American graduate student at Leeds in the late 1950s when he bough this shuttle. | |

|

Woolen Cloth Finishing Before and After The Industrial Revolution

|

|

Teasel Teasel was introduced to the United States from Europe as a crop to brush the nap on cloth. It now grows wild along many of the highways in the United States and is considered a pest. This photo of teasel was taken at a rest stop along the Ohio turnpike. |

| Photo collection of Maggie Land Blanck Woolen cloth was loosely woven. To finish the cloth it was fulled by a process of applying moisture and pressure. After the cloth was fulled it was stretched to dry. Next the cloth was dressed. Teasel, a thistlelike plant, was used to brush the cloth and bring up the nap, which was then cut close to the surface of the cloth. Teasel initially made the transition into industrialization. The earliest napping machines used teasel set in the brushing apparatus. Later machines used little wire hooks. The teasel burr is still considered by some as superior to the wire brush for giving the cloth a better finish. | |

|

Industrialization of the Weaving Industry in The Area Around Batley and Birstall Parishes The first woolen mill in Liversedge was built by Thomas Oakes in 1695. William Wilcock of Stubley Farm, Heckmondwike, and Israel Rhodes of Liversedge were manufacturing textiles for the "American market" at Miln Brigg Mill in Liversedge in 1770. William Cartright of Rawfolds Mill between Liversedge and Cleckheaton was the first textile manufacturer in the area to experiment with mechanized cloth finishing. In 1809 he introduced finishing machines that were driven by a water wheel. The results were so satisfactory that he decided to dispense with the hand methods entirely. Cartwright's success caused jealousy and alarm among the neighboring master-finishers and concern among the employees about the future of their jobs. See the Luddites below. |

|

| |

|

The early mills were powered by water.

I do not know if this old mill at Chagford Devonshire was

used in connection with the woolen industry. Water mills mills were also used to grind flour.

|

| Stereocard collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

| |

|

Water Mill Westmoreland From an original drawing by

1834

|

| Print collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

| The Luddites and Their Opposition

to the Industrialization of Woolen Weaving

In the early 1800s the economy in England was bad . Embargoes during the war with Napoleon caused a rise in prices. Unemployment was high. As a response to the bad economy and because they believed that industrialization was a cause in the rise in unemployment, members of the Luddite movement deliberately smashed machinery in the industrial centers of the East Midland, Lancashire and Yorkshire between 1811 and 1816. Frank Peel, a local Yorkshire historian, wrote a book about the Luddite movement in Yorkshire. The Rising of the Luddites Chartists and Plug Drawers (forth edition 1895) was originally published in a series of articles in the Heckmondwike Herald and Liversedge Weekly courier between January 25 and August 6, 1787. These articles were first reprinted with some variations as a book in 1880. Peel says that the long Napoleonic wars in Europe which "ravaged for half a generation" had brought "misery and wretchedness" and "the hard pinch of poverty was now felt in many a dwelling where it had hitherto been a stranger." One of the new machines that was introduced was the cloth frame (AKA, cropping or shear frame). Cropping was one of the final stages in cloth production. After the cloth had been fulled it was brushed and the nap was cut off with hand held shears. Cropping by hand was a slow and costly method. In addition, it was difficult work and the cropper developed a "hoof" on his right wrist. Apparently a person could by identified as a cropper solely by this "hoof". Peel says it was "very painful for learners to handle the shears until the wrist has become hoofed". Before the introduction of the cloth frame in local mills, there were numerous small cropping shops in the area. There was plenty of work and a cropper could earn a good wage. In 1809 William Cartwright, a West Riding cloth manufacturer, introduced cloth frames (driven by water mill power) at his factory in Rawfolds near Cleckheaton. These cloth frame enabled two shears to simultaneously crop two pieces of cloth which had been fixed on shear boards. The man (or boy) in attendance only had to stand and watch until the cut was completed. He then moved the cloth forward and repositioned the shears. The procedure was faster and easier and the job became one of "care and watchfulness" instead of hard labor. The problem, of course, was that one machine could do work that had previously occupied four men. This meant that three men were out of work at a time that the economy was hard hit and when there were no other jobs available. Prior to the introduction of the cloth frames, most cloth dressing shops were small establishments employing three or four men. Peels says, "Before the advent of Mr Cartwright's new frames, work was plentiful · and the men received good wages, but, as the machinery began to be used, the little masters who adhered to hand cropping found it more and more difficult to carry on business at a profit, the result being that the men gradually lost their employment, and many of the workshops were, after a struggle closed altogether.Initially, Cartwright's was the only mill in the area to introduce this new machinery, the rest of the mills continued to finish cloth using the old method of hand cropping. The cloth dressers in the area refused to work with the new machines and showed their animosity by "covertly injuring" the machines when they had the opportunity. In 1811 there were a series of riots and uprisings in some of the larger commercial centers in the north of England. Peel says that the local croppers "watched the gradual decay of their industry in sullen despair at first, but the news of the turbulent demonstrations at Nottingham, where the lace makers had risen against a frame of another character which threatened to destroy their trade, had stirred them strongly and the more violent spirits among the local cloth finishers began to urge that similar measures should be taken against the cropping frames introduced by the Yorkshire manufactures."According to Peel the finishing shop of John Wood at Longroyd Bridge near Huddersfield became the head quarters for the leaders of the Luddite in the West Riding. Most of the Luddite action in the West Riding took place around Huddersfield and much of it was directed toward William Cartwright. In February 1812 a meeting of cloth finishers from Birstall, Cleckheaton, Gomersal, Heckmondwike, Liversedge and adjacent places, took place at the Shears Inn, Hightown, in Liversedge. The cloth finishers learned that another patch of finishing frames were being sent by wagon to Cartwright's mill. Some men decided to waylay the wagons and destroy the machines. These "Luddites" marched in "armies" carrying guns and ammunition. The guns and ammunition had been obtained in raids of homes in the area. They also carried hatchets which they used to destroy the machinery. According to Peel these bands of men were made up of men from Huddersfield, Dewsbury, Heckmondwike, Mirfield, Halifax, Elland, Brighouse, Morley, Birstall and Gomersal. They waylaid the wagons and smashed the machinery. The military was sent to the district. Other incidents occurred near Huddersfield in March, 1812 and at Horbury on April 9, 1812. The Luddite rioters made an historic attack on Cartwright's Rawfolds Mill on Saturday, April 11, 1812 when about fifty masked and armed men attacked the mill at night. All of the widows of the first floor and many on the second floor were broken and some other damage was done to the mill. The Luddites, however, were not able to break into the mill. Cartwright had prepared for the attack by fortifying the mill and retaining several armed men on the premises. Two of the attackers died, and many others were wounded, before they realized the hopelessness of the situation. None of Cartwright's men were injured. This was the first time a mill owner had taken such a stance against the Luddites and it checked the practice of frame breaking for a while. Some of the Luddites involved in the incident were brought to trial. Several were convicted and hung at York. Cartwright became a hero to the other manufacturers in the West Riding, who presented him with a sword and three thousand pounds. However, the local population ostracized him to the point that he stopped attending church and had the local minister to his house to deliver the Sunday sermons to his family and servants. Cartwright's story was part of the plot of Charlotte Bronte's novel Shirley. The novel is overly romantic and deals only peripherally with the Luddite movement and the incidents in Huddersfield. Although there were many cloth finishers and others in the cloth industry who did not participate in the Luddite movement, there were many who sympathized with it and hoped for its success.

The Economy in England 1806-1846 At the time of the Luddite uprisings George III was insane and his son was acting as regent. Napoleon, who had come to power as a reformer after the French Revolution, was at the zenith of his power. England and her allies had declared war on France in 1803 but by 1806 Napoleon controlled all of Europe and England remained alone in the fight against France. The aristocracy in England had undertaken the war with Napoleon in an effort to crush French liberalism and return a king to the thorn in France. Napoleon had issued an economic blockade against English goods. The commercial and manufacturing sectors in England were in a dire financial situation. Defective harvests in England had caused the price of grain to rise. The Corn Laws which had been passed in England in 1436 limited the import of wheat. In the meantime the English government was sending money abroad to support their allies in the war against Napoleon. The poor, without work were parading through the streets "in gaunt famine stricken crowds, headed by men with bloody loaves mounted on spears crying in plaintive, wailing chorus for bread."In Nottingham about 15,350 people, about half the population, were at one time or another receiving assistance under the Poor Laws. Things were not so bad in Yorkshire, but there were many people seeking public assistance. Napoleon was finally defeated in 1815. However, the economic situation in England did not improve and things were still bad economically when Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837. In 1839 trade was still bad , the cost of bread high, and the working class was in a desperate state, especially in Lancashire and the West Riding. Wages were low, prices were high and many people in the West Riding were unemployed. In the early 1840s the Chartist began a movement for Parliamentary reform. Riots broke out in Leeds, Wakefield, Dewsbury, and Halifax. Mobs descended on Cleckheaton, Batley, Birstall, Littletown and Heckmondwike. In many places in the West Riding clothing district attempts were made to stop the factories by pulling the "boiler plug" to bring all labor to a standstill. The idea was to show the capitalists how much they depended on the working class. Many local men and women were involved in these riots. However, according to Peel some of the local factory workers defended the mills which employed them. The abolition of the Corn Laws in 1846 inaugurated an era of cheap bread. Free trade loosened the ties of commerce and working men, now better feed and better clothed, ceased to agitate against the government. Peel says of the working class before the repeal of the Corn Laws, "Oatcake was then the "staff of life", and oatmeal porridge an article of constant and universal consumption once a day at least, often twice, and not infrequently three times. Butchers' meat was a luxury in which they could seldom indulge, and then only to a very limited extent. Manufacturers everywhere were availing themselves of the many wonderful inventions that were being brought out for cheapening labour, and as the new machinery threw thousands out of employment when extensively introduced, the poor, misguided wretches, who could not understand how that could be a benefit which deprived them of the means of earning a livelihood and reduced them to beggary, met in secret conclaves, and resolved in their ignorance to destroy them. Had they been better instructed, they would have known that it was their duty to lie down in the nearest ditch and die". Excerpts From A Letter On the Worsted Trade From Sir Henry Mitchell to the Government in 1884

"Forty years ago the hours of labour in our factories were seventy-two per week, and a very small number of our operatives received any education, except those working half time; now the hours are reduced to fifty-six and a half per week, and all are compelled to go to school until thirteen or fourteen years of age. Although the hours of labour have been so much reduced, there has been no perceptible falling off in the production of goods, as the speed of machinery has been increased, and the hands are able to give more attention to their work and to turn out as much as at any former period. There has also been a marked decrease in mortality of both children and adults....."

Long, Boring Hours, Low Wages and Indebtedness In 1867 a high proportion of skilled workers were men who had worked a seven-year indentured apprenticeship. Such men often made or mended their own tools. And drafted their own designs for machinery. Traditional apprenticeship was in decline from the 1870s. At first because journeymen found that they could demand high wages without completing their training, later because the wide spread use of machinery rendered their skills obsolete.

"At first the factory system bore very hardly upon the operatives. Even children of eight and ten years of age were kept at work fourteen to sixteen house a day, and many over-greedy employers adopted the truck system, compelling their employees to purchase the necessaries of life at shops opened by the masters."Between 1870 and 1907 mining, metallurgical industries and heavy engineering outstripped the manufacturing of textiles, which had been the leading sector in the earlier period of industrialization. In many industries personalized skills gave way to electrically powered tools, production lines, machine-minding and semi-skilled employment. In the textile industry there were limited technical innovations after the 1880s. This was also the period of the last of the hand loom weavers.

|

| The Mills |

|

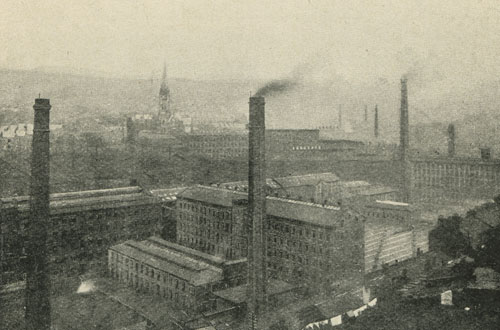

| Collection of Maggie Land Blanck Mills at Cleckheaton, circa 19150 |

| Pollution | |

| |

| Yorkshire West Riding By B Hobson, 1921 Halifax: A factory town Another downside of the developments of factories was the pollution caused by the fossil fuel.

| |

| |

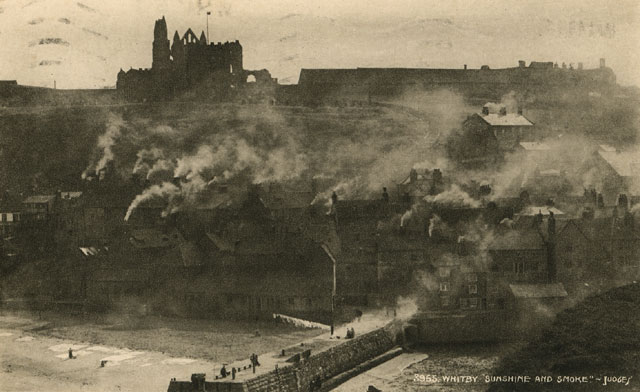

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck

Whitby "Sunshine and Smoke" posted in 1929

"Regret for sylvan scenes supplanted by smoking chimneys and fouled streams is lost in contemplation of the gain such development produces in strengthening and enriching the nation, and conferring means of comfort upon large masses of its people." "Calder means white, now a sad misnomer for passing though the heart of Yorkshire coal fields the stream is fouled almost from its souse by the sewage of many a busy town." | |

| |

| Print collection of Maggie Land Balnck

Manchester: From Kersal Moor, engraving Edward Goodall (1795-1870) of a Wylde painting commissioned in 1852 by Queen Victoria

| |

|

| |

| Wages in the Cloth Industry in Batley in 1858

Samuel Jubb writing in 1858 about the cloth industry gives the following statistics on employment in Batley:

|

| Occupation | No. of people employed | Wage per week |

| Ragsorters, women | 500 | 6 s 6 d |

| Slubbers | 220 | 30 s |

| Piecers, machine attendants | 148 | 6s |

| Piecers, boys and girls | 70/140 | 1s to 3 s |

| Overlookers | 30 | 35 s |

| Hand loom weavers | 1260 | 18 s |

| Power loom weavers | 500 | 9 s |

| Drawers | 70 | 30 s |

| Robert Walker, who lived in Birstall Parish and died in 1857, had been both a slubber and an overlooker. John Land was one of the 70 drawers listed by Jubb. In 1861 William Law was a hand loom weavers and his daughter, Mary Ann, was a power loom weaver. |

|

The Leeds Industrial Museum is a located in the old Armsley Mill on the outskirts of the city of

Leeds.

Among other collections, the museum contains textile machinery and explains the story of the

woollen industry in the area. To see photos from our visit in 2002 and some addition pictures of

weaving in the industrial era go to Armley Mill

To go to the Armley Mill Museum site maintained by the city of Leeds, click

HERE

|

|

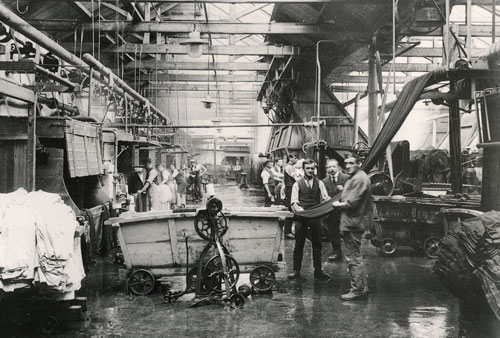

The Dyehouse At Salt's Mill, Saltaire, 1920 |

| Photo collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

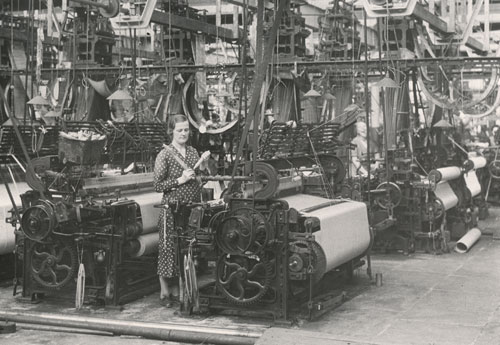

A weaver loads a pirn of weft thread into a shuttle, 1940s |

| Photo collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

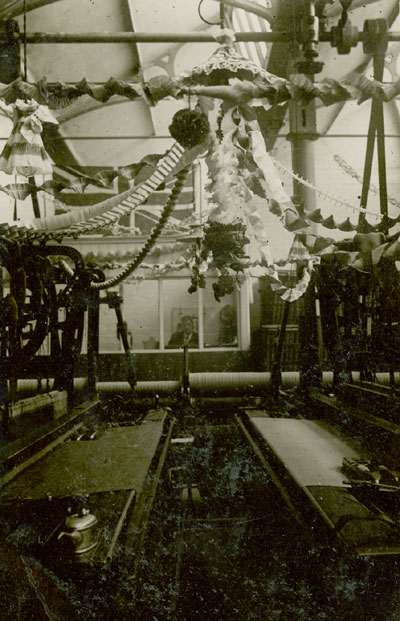

Someone has written on the back in pencil "Hunslet Mill 1918 Dogsons and Hargreaves Mill Hunslet, near Leeds. The decorations are because there is going to be some important visitor, perhaps a "royal visit". |

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

|

|

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck

Interior Cotton Mill, Shipley circa 1900. Again the mill room is decorated for some important event. | |

| |

|

|

| Photo courtesy Richard Whitehead, August 2011

Dewsbury 1949 | |

| |

|

|

| Photo courtesy Richard Whitehead, August 2011

Headfield Mill Dewsbury | |

| |

|

|

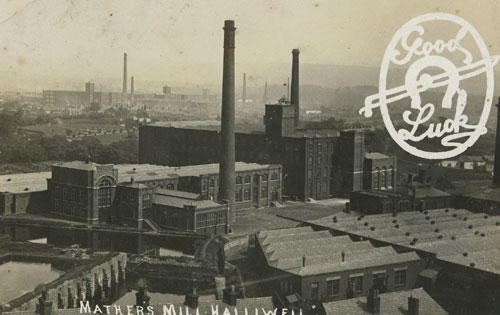

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck

Exterior Mather's Mill Halliwell, not posted | |

| |

|

|

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck

Mill workers, Clampton Bros., Richardshaw Lane, Pudsey | |

| |

|

|

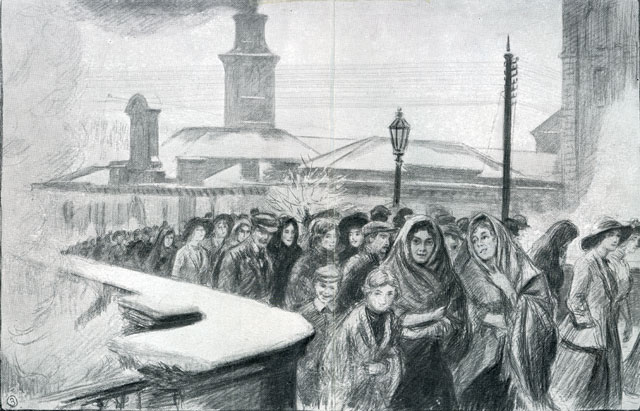

| Print collection Maggie Land Blanck

The Graphic February 1 1913 - "In the City of the Sheep: A Town Founded Upon Wool,

Scenes in Bradford, Yorkshire's Great Cloth-Making Centre,

Which Supplies the World With Worsted Cloth"

The Town of Saltaire Leaving The Mills, Which Employ 3,000 Hands Were the children in this image employed in the mill? Saltaire Mill still stands. Go to Salts Mill, Saltaire - West Yorkshire for information on the current use of mill. | |

|

|

| Photo collection Maggie Land Blanck

Raventhrope mill fire. Fires were a constant danger in the West Riding Mills due to the highly flammable materials which were stored in them.

Charles Street in Ravensthorpe was/is between Mirfield and Dewsbury.

| |

|

| Postcard collection of Maggie Land Blanck Airedale Mill Fire, Kildwick 31/3/06 |

| |

| |

| Postcard collection Maggie Land Blanck

Reconstruction of This Part of the Gomersal Mills, after fire April 25, 1913 For Messrs, Thomas Burnley and Sons Ltd. (Establisher 1752) Round about Bradford By William Cudworth, 1876, Google Book The Burnleys have been in the worsted trade for four generations. As early as 1752 the business was carried on by William Brunley; in 1800 by William Brunely & Sons, and afterwards by James Burnely and his sons Thomas and William. Since the year 1855 the business has been carried on by the firm of Thomas Burnley & sons, the present partners being Thomas and Frank Burnely, by whom the works have been considerably enlarged and completely remodeled. This firm is now the largest ratepayers and employers of labour in the village."The Burnleys lived in a large mansion, perhaps the grandest in Gomersal, called Pollard Hall on Oxford Road. Much of the original building dates to 1659. The Burnleys originally occupied the hall as tenants. William Burntley moved into the hall in the mid 1700s long before his factory was built. The Burnleys purchased the property in 1843. At the time of the purchase the property included a dyehouse and spinning shop. Some work, such as dyeing and finishing, was done in the hall by the Burnleys and their employees. Spinning and weaving was done the cottages of the local hand spinners and hand loom weavers. The Burnleys built thier first mill at Hill Top in 1850. In 1851 the mill was called Gomersall Mills and Thomas Brunley manufactured cloth, blankets, worsted and yarn.

| |

| To see colored copies of the pictures by George Walker (This page also includes more information on the weaving industry.) go to Life in Yorkshire |

| See also Crime in Yorkshire and Transportation in Yorkshire |

| With industrialization came the need for greater sources of power which, in turn, spurred on an increase in coal mining . The West Riding was rich in coal fields which helped to fuel the growth of industrialization in the area. For images of the collieries go to Collieries and Coal Mining |

| If you have any suggestions, corrections, information, copies of documents, or photos that you would like to share with this page, please contact me at maggie@maggieblanck.com |

| Please feel free to link to this web page.

|

| ©Maggie Land Blanck - Page created 2004 - Latest update, March 2016 |

| RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE |