| Scribner's September 1877, The Immigrants Progress | |

| HOME | |

| BLANCK INTRODUCTION | |

| GOEHLE INTRODUCTION | |

| PETERMANN INTRODUCTION | |

| LAND INTRODUCTION | |

|

Giles and His Friends at the Village Inn |

|

There is scarcely a hamlet in all England which has not been invaded by the emissaries of one of the great steamship lines. Either in the tavern, the reading room, or the apothecary's shop, a bold red-and-black placard is displayed, bearing the names of half a dozen vessels and the dates of their sailings. Honest Giles, sitting of an evening in his accustomed place by the fireside of the village inn, has it constantly before him, and makes it the text of many long chats with his neighbors about the wonderful land in the west. It is loosely tacked to the edge of a shelf, and rustles and ripples in the breeze ever time the door is opened to admit a new-comer. The farrier's son is in America, and the glowing accounts he sends to his father of his new home are invariable read aloud to the assembled company. The general opinion of the villagers is favorable to " the States" but the sexton- a bluff, hectoring fellow with pronounced views in favor of church and state- bears no love for this land of liberty and law. Sometimes a queer paragraph appears in the newspaper relating an instance of lynch-law in Arkansas, or of party politics in Louisiana, and then the sexton cries out against Americans as a boastful and corrupt people. He succeeds in turning the current against them for a few days, but when next week's paper comes, Giles reads the eloquent words of praise spoken by Mr Froude, Mr Foster, Professor Huxley or Professor Tyndall, and is re-established to the old faith.

Some of the old villagers who formerly sat around the fire and drowsed away all the evenings of the year are settled in Australia, Canada or the United States. Letters often come to the village from them, with small amounts of money or photographs which represent the writers as brighter looking and in better dress than they ever appeared at home. The most encouraging accounts of all come from "the States", and when honest Giles is sorely pressed with difficulties, and Mrs Giles is fading for want of proper nutriment, and her boys are running to waste, after long deliberation and many regrets Giles resolves to sell his little all and embark for New York. When he announces his resolution to his cronies at "the Kings Arms," the hostelry is stirred by a ripple of excitement such as it seldom experiences, but as the evening advances Giles is left to himself, and, contemplating the steamship placard through the clouds of his tobacco smoke, the gaudy printing reveals a series of dissolving views of happiness and prosperity awaiting him across the sea. He selects one of the Liverpool steamers as they have the best reputation and are the most convenient. His choice is the common one. More than half the whole number of emigrants coming to the United States, arrive at New York in vessels from the former port. One morning, then, Giles finds himself surrounded by his numerous family and baggage on the Great Landing-stage at Liverpool. The vast floating pier is crowded with departing emigrants, who are as confused and frightened as a flock of sheep. The majority are English, Irish and Scotch; but there are also bearded Russians and Poles, enveloped in frowzy furs; unclean Italians, some of them carrying dingy musical instruments, with a considerable number of Germans, It is a curious fact, by the way that as many Germans emigrants come to America via Liverpool as come in the German steamers direct form Hamburg or Bremen. They are conveyed to Hull by water, and thence across England to Liverpool by rail. Mr Giles is a little dismayed by the appearance of his prospective traveling companions. A good many sinister men and loose women are noticeable, and Giles thinks sadly of the distant corners of the earth which must have been swept out in the gathering of them. But among the unclean outcasts the sturdy plowman rejoices to find a few who are like himself and his wife- neat in dress and cleanly in person. The busy, gold-laced interpreters and emigrations agents treat all alike, however, answering questions gruffly or not at all, and often causing the hot blood to rush madly into Giles' indignant face. After much worry and noise, the emigrants are taken from the landing-stage by a small steamboat and conveyed to the large vessel anchored in the stream. As they pass up the narrow gangway the tickets are scanned by one officer, while another orders "single men forrad," and "single women aft." So the crowd is divided into two streams, and in the course of an hour the decks of the big steamship are reduced to a condition of order. Each emigrant has a contract ticket which stipulates for his transportation to New York in consideration of four, five or six guineas, according to the current rate of fare. The company engages to provide a full supply of wholesome provisions, cooked and served by its stewards, and the passenger is required to provide himself with bedding and cooking utensils. The weekly allowance of food for each adult is prescribed by the government and printed on the contract ticket as follows: "Twenty one quarts of water, threes and a half pounds of bread, one pound of wheaten flour, one pound and a half of oar-meal, rice and peas, two pounds of potatoes, one and a quarter pounds of beef, one pound of pork, two ounces of tea, one pound of sugar, two ounces of salt , pepper, mustard, and vinegar. The emigrants are berthed by the steerage stewards, and are then marshaled on deck again under the scrutiny of a government inspector who is in search of infectious diseases. Their tickets are also examined again, and some would-be stowaways are sent back to the shore in the little tender. Piteous complaints are made by some unfortunates among the passengers that they have been robbed of their money in the town, or that they have lost their tickers; but their cries are unavailing and are drowned in the roar of escaping steam and the clangor of the bells. By and by the cabin passengers are brought on board, and with a full cargo and a thousand souls the great steamer leaves her moorings. Let us preface all that we have to say against the manner in which Giles and his fellow-voyagers are treated with this frank admission: Constant improvements are being made in emigrant passenger vessels. Less than a hundred years ago the great majority of emigrants were very poor,- so poor, indeed, that they could not prepay their passage. Accepting advances, they were bonded to the ship-owners, who derived enormous profits form the sale of their bodies into temporary slavery. Charles Reade had given a vivid description of the emigrant traffic at this period in his delightful story of "The Wandering Heir." Whenever, a vessel arrived at Philadelphia or New York, the steerage passengers were sold a public auction to the highest bidder. The country people either came themselves to purchase, or sent agents. Parents sold their children, that they might remain free themselves, and families were scattered never to be re-united. Old people and widows did not sell well; while healthy parents with healthy children and youths of both sexes, always found a ready market. When one of both parents died on the voyage, the expences of the whole family were summed up, and charged to the survivor or survivors. Adults had to serve from three to six years, and children until they became of age. Runaways had to serve one week for each day, one month for each week, and six months for each month of their absence. Technically, the emigrants were called "indentured servants" but in effect they were slaves. The last sales of emigrants took place in Philadelphia during the years 1818 and 1819. The American government then interfered with the traffic, and encouraged the emigration of a superior class of people. But the accommodations for emigrants remained shamefully defective, and nearly twenty out of every hundred passengers died at sea of fever or starvation. The steerage deck was usually about five feet high, without ventilation or light, and in this space the bunks were ranged in two or three tiers. The health of the passengers was further impaired by another evil which, up to a very recent date, prevailed on board emigrant vessels. The emigrants were expected to provide and cook their own food. Many embarked without any provisions at all, or an insufficient quantity, and others found no opportunity to cook what they had. On the upper deck of the vessel there were two small "galleys, " about five feet wide and four feet deep, each supplied with a grate, and these were the only arrangements make for cooking the food of several hundreds persons. Thousands never lived to se their destination. Out of about ninety-eight thousand laborers sent from Ireland to Canada after the famine of 1846, nearly twenty-five thousand perished in consequence of the poor rations and defective ventilation of the ships. Later still, in 1868, on one vessel alone,- the "Leibnitz," from Hamburg,- over one hundred passengers died, out of five hundreds. Giles lives in better days. The mortality on vessels bringing emigrants to New York seldom exceeds one and two-thirds per cent., and in some instances is no greater than one-eighth per cent. But Giles is dissatisfied and we mean to see whether or not he is justified in his ill-humor. The great steamer soon bids good-bye to the Mersey, and rolls on her way through the cross waters of the Irish Sea towards Queenstown. The sky is overcast and sullen; rain and spray patter on the deck; and wind shrieks in chilly blasts. Between the gray clouds overhead and the gray waters beneath, the black hull of the steamer tosses and groans uneasily. The great passengers of the first cabin and the small passengers of the steerage are afflicted with a common complaint, and are prostrate in their berths, or in a humiliating attitude on deck. The weather is always the same in the Irish Sea-always cold, wet, and windy. So while the cost acute of Giles' present miseries may be alleviated, it cannot be altogether averted. The emigrants are roughly driven hither and thither, and urged into their places by much hard swearing and abuse. Neither officers nor men consider them worthy of the least respect, and treat them as a drove of cattle. Some of the vagabonds and outcasts submit without complaint; but decent laborers, like Giles, fell indignant and are inclined to resent the savage words. Giles can scarcely believe that the steerage is intended to be a house for human beings. It is cold, dark, and - at the very outset of the voyage-foul-smelling. It extends nearly the whole length of the vessel beneath the saloon deck, and is devided into gloomy compartments. In each compartment there are four tiers of berths or bunks, two on each side. The lower tier is about two feet from the deck, and the upper tier is about three feet from the roof. The height of the steerage is about ten feet, which is advertised as unusually lofty by the steamship owners. In each tier there are six berths, eighteen inches wide and six feet long, formed of wooden boards, smelling faintly of chlorate of lime and carbolic acid. One-half of the passengers have never had softer or more spacious couches, and accept their lot in good part; put other half have been used to a comfortable home, and are wretched. There is not thorough classification of the passengers. The single men and women are separated; but Poles, Germans, English and French are thrown together without discrimination. A cleanly, thrifty English or German woman is berthed next to a filthy Italian woman. Mrs. Giles thinks her bed would be hard enough, even though it were isolated, but her misery is intensified by the presence of a dreadful hag in the next berth. A dreary sight meets Giles as he comes into the steerage from the open deck. A feeble light streams through the ports, which are occasionally obscured by a wave dashing against them on the outside. He can dimly see the women and children sitting or lying in their berths, and hear the children's cries. The stewards are fussing about, or making coarse jokes. By and by preparations are made for supper, of which only a few eat, and when the meal is over, the tables are raised to the roof, leaving a clear space in the center of the steerage. Anon a few oil lamps are lighted, to be extinguished again at nine o'clock. The massive vessel quivers as she lurches between the waves, and her engines throb unceasingly as the long night passes away. Some time during the next morning she enters the beautiful harbor at Queenstown, and a few hundred weeping, laughing, forlorn Irishmen are introduced into the already overcrowded steerage. At sunset she has passed the Fastnet Light, and the ocean voyage has begun.

|

|

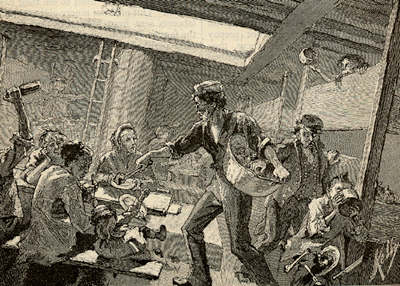

Dinner in Steerage |

|

Giles is probably too much occupied with other grievances for thought about the life saving equipment of the vessel, and would have no means of satisfying himself were inclined to inquire. The vessel herself is as stanch as iron and steel can make her, and the line to which she belongs has never lost the life of a passenger through the carelessness of its employees. Man has been faithful and fate kind to those old ship-owners at Liverpool. No serious accident has ever happened to their steamers, which have weathered the cyclones of summer and the continuous gales of winter for many years. But what if disaster should befall? Has every provision that human forethought and ingenuity could devise been made to meet it? The largest steamers in the trade carry ten open boats, each of which, under favorable circumstances, might accommodate about seventy persons. But when are circumstances so favorable that all a ship's boats can be launched successfully in a time of panic? Two or three are almost invariably capsized or dashed to pieces against the iron sides of the vessel; and even supposing that all are launched, what then? During a busy season, some of the larger steamers from Liverpool often bring as many as fifteen hundred emigrants to New York at a time. In some instances seventeen hundred persons, exclusive of crew, have been packed in the steerage of one vessel. The ten boats will carry seven hundred at the most, and there are not rafts or buoys on board for a hundred more. The consequent loss, in care of fire or wreck in mid-ocean, would include the greater part of both passengers and crew.

The truth is, the owners trust of good luck in contemplating the subject, or treat the matter with indifference. The captains and officers are compelled to assume the responsibility. The master of a steamer told the writer that in leaving Liverpool with over a thousand emigrants on board, he remarked to the agent on one occasion how improbable it was that a single life would be saved, where it ever necessary to abandon the ship at sea. The agent dismissed the matter with the cold observation that the captain took a morbid view of things, and distressed himself about disaster which would never happen! Giles and his friends, who have never been afloat before in the lives, are slow in settling down to the routine of the voyage. They complain to the captain of the narrowness of their quarters, the insolence of the stewards, and the quality of their food; and the captain listens to them, or growls at them, according to the mood he is in. While the weather is fine, their sufferings are not very great. Three meals are served every day, and both in quantity, which is unlimited, and in quality, which is variable, the rations are better than the law demands. Breakfast, at eight o'clock, consists of oatmeal porridge and molasses, salt fish, hot bread, and coffee; dinner, at twelve, of soup or broth, boiled meats, potatoes, and bread; and supper, at six, of tea, bread, butter and molasses. But the manner in which the meals are served is careless and uncleanly. The beef, soup, and porridge are placed on the table in grea , rusty-looking tins, which need scrubbing; and the passengers scramble for the first choice, often using their dirty fingers instead of their forks, in making selection. Mrs Giles finds her appetite gone after watching a filthy rag-picker plunge his hand into a dish of meat for a tender piece. The stewards themselves are greasy, and want washing. The potatoes are bad, and the bread is not baked enough. Still, while the sea is calm., Giles can take his family on deck and brace them with the glorious fresh air, which brings roses to pallid cheeks. Indeed, the emigrants are quite merry on deck during a warm summer's day. Some of the squalid Italians are dragged from their suffocation retreat over the grating of the engine-room, and induced to give a concert with their harps and violins, to which the cabin passengers liberally subscribe. Card-parties are formed and checker-boards roughly made for the occasion. Giles lies basking at full length on a hatchway, and dreaming over and old newspaper. It is when a storm comes that the emigrants suffer the most. The hatches are battened down, the ports screwed in their places as tightly as possible, and the companion-ways closed. So long as the sea sweeps the decks, Gilles and thirteen hundred others are confined to the steerage. It may be for a day, or two or three days. Each hour the atmosphere becomes more close, and in twenty-four hours it is loaded with impurities. The meals are served irregularly, or not at all, and the food is not cooked enough. In the darkness the ignorant and timid lose control of themselves, and pour out imprecations and prayers in shrill chorus. The terror spreads to others, and the bravest quail as the shrieks grow louder. The greater the number of emigrants, the greater the confusion and the worse the atmosphere. We have known of instances in which the sailors have refused to enter the steerage for the purpose of cleaning it after a storm until the captain fortified them with an extra supply of grog. And sailors are not ridiculously sensitive, nor are captains in the habit of indulging them without reason. Giles is pale and feverish when he reaches the open air again, and his wife and children are too weak to stand. The deck is still wet and the wind boisterous; but he cannot endure that "black hole" of a steerage. The thought of the filth he has seen and the dread of contamination sicken him. The company is to blame, he thinks, for crowding so many people together; but the habits of some of the emigrants are even more to blame than the overcrowding. The Italians will not wash themselves, and cling to their berths until they are peremptorily ordered ut by the captain. They neglect ever provision made to insure their personal cleanliness, and they excite little sympathy when they are brought on deck and thoroughly drenched with water from the fire-hose. In nine or ten days the voyage draws to a close, and hope is revived in Giles' breast. He has very hazy ideas of the country he is approaching, and believes that its characteristic features are Indians, buffaloes, and log cabins. Very likely he expects to obtain a view of the Rocky Mountains from Chicago, see war-chiefs in their paint on the streets, and hunt for his supper before he eats it. He has heard much about the great cities, the wealth and liberality of the people, the profligacy of municipal governments; but it never enters his head that New York has any of the magnificence of London. His surprise is unbounded when the steamer arrives at Quarantine. The cultivated lands on the heights of Staten Island and on the Long Island shore, the tasteful houses, prettier to his eyes than the English villas, the appearance of wealth, comfort and beauty on each side of the Narrows, astonish him and excite his warmest admiration. If he is fortunate, the day is warm and sunshiny, and tempered by a delicious breeze coming from the sea. That cloud which looms at the head of the bay,- that, he is told, is New York, the gate-way to the land of promise, and he points it out to Mrs Giles and the children to their intense satisfaction. |

|

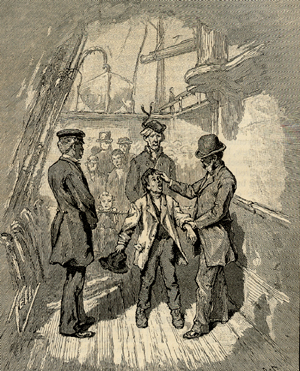

Inspector at Quarantine |

| A little tow-boat brings the doctor on board,-not the ship's doctor, but the health-officer of the port, who inspects the steerage and the emigrants. As there are no cases of an infectious disease, the steamer is allowed to proceed to the city, and then another little steamboat appears, bringing the boarding-officer employed by the Commissioners of Emigration. The boarding-officer is an officious Irish-American gentleman, who ascertains the number of passengers on board and their health. He is also instructed to examine the steerage and to listen to all complaints made; but he retreats below as soon as he comes on board, and we are much mistake if he may not be found at the bar taking a quite "nip" with the chief steward. Meanwhile the emigrants on deck are looking wistfully toward the city, with its high roofs, spires and towers. Many of them are anxious and sick at heart, almost afraid to enter the new and unfamiliar would now that they are at its portals. Some happy ones expect friends to meet them and know all about the beneficent offices of Castle Garden, which they explain to others who are not so well informed. By and by the trees and lawns of the Battery Park come into view, with the curious looking building, in the form of a rotunda, at the water's edge. The steamer's pulse ceased to beat, and several large barges are towed alongside. The baggage is brought from the hold and transferred with the emigrant passengers to these tenders. There is the some confusion and uproar as at the outset of the voyage. The bewildered people are browbeaten and driven about in the most inconsiderate manner. A loud laugh is heard for an instant. An old lady from Ireland has put her tin cooking utensils underneath the cord that bind her heavy trunk. As the trunk is tossed down the gangway, the sailors fail to keep "this side up with care," and saucepans and basins suddenly collapse. As soon as the barges are loaded, a steamboat takes them in tow, while the great steamer proceeds to her pier in the North River. |

|

All There |

|

Castle Garden has been famous for generations. First it was a fort, and then it was converted into a summer-garden for the sale of chocolate, soda and ices. In 1832 it was the scene of a grand ball given to the Marquis Lafayette, and in 1843, a reception was given to President Tyler within its walls. Afterwards if became a concert-hall, in which Jenny Lind and many other celebrated singers make their first appearance in America.

The Board of Commissioners of Emigration was created, in May 1847, and Castle Garden was afterwards selected as a convenient suitable entrepot for immigrants, and such in remains. It was partly destroyed by fire on July 9, 1876, but it has been rebuild with a few changes which do not materially alter its appearance. The lower walls are the same that formed the old fort, and the embrasures, though which the cannon peeped, are sometimes selected by immigrants for smoke and rest, or meditation. From May, 1847 to March 20, 1876 the laws of the state required the owners or agents of vessels arriving at the port with immigrants to give a bond of $300 for each passenger, conditioned to indemnify every city, town, or county in the state against any charge on account of the relief or care of the passengers during the first five years of his residence in the country. The same laws enabled the owners or agents to commute the bond by paying a certain sum known as "head money" (which varied at different times, the highest being $2.50 and the lowest $1.50) to the Commissioners of Emigration, whose duty it became to pay expences incurred by the immigrant in any poor-house or hospital, owing to his infirmity or poverty. The large steamship companies where opposed to the exaction, and on March 20th, 1876, they obtained a decision through the Supreme Court of the United States that the law was unconstitutional and void. The expenses of the Commissioners for the current year (1877) are defrayed by an appropriation of $200,000 made by the state; but an effort will be made at the next session of Congress to obtain further authority for the collection of head-money. The barges are soon moored to the wharf at Castle Garden, where the custom-house officers are in waiting to examine the baggage. Battered old chests, barrels, and great bundles of clothes and bedding are packed together much against the wishes of their owners, who are in terror of losing all their worldly treasure. The officers then set to work, with turned-up sleeves, and faces expressive of repugnance. Some of the bundles are uninviting, but they are explored and turned upside down and inside out with a degree of energy and speed highly creditable to the inspectors. Some of the unmarried men have no baggage at all, except a small bundle tied in a handkerchief and slung over a stick. Some forlorn women who embarked at Queenstown, are without bonnets, and have no shawls or mantles. The whole wealth of the Italians consists in their organs, harps, fiddles and the clothes they wear. They have traveled from country to country, and from town to town, earning their bread on the way, and in the same manner they will travel to their destination in America. Other immigrants with families are overloaded with baggage and have large sums of money in their pockets. At one time all passengers were questioned at Castle Garden as to the amount of money in their possession; but they scarcely ever gave truthful answers. It is assumed on creditable evidence, however, that one hundred dollars at least, is the average amount in the possession of each person, and that the average quantity of property brought by each is worth fifty dollars more. During 1869, two hundred and fifty-nine thousand immigrants arrived at Castle Garden, and thus the amount added by them to the national wealth was almost equal to thirty-nine million dollars. Large as this sum is it becomes trifling in comparison with the capital value of the immigrants labor. A well-known social economist estimates the capital value of the male laborer at one thousand five hundred dollars, and the capital value of the female at seven hundred and fifty dollars, making average value of person of both sexes eleven hundred, and twenty-five dollars. Between May, 1847 and January, 1870, four million, two hundred and ninety-seven thousand immigrants were deposited in New York. Adding to the capital value of each immigrant the estimated value of his personal property, we find the immigration increased the national wealth by more than five billions of dollars in less than thirty-three years. The total immigration into the United States for several years previous to 1874 was at the rate of three hundred thousand persons a year, and the country gained nearly four hundreds of millions of dollars from the traffic, or more than one million a day. Less than five per cent. of the whole number of immigrants are unproductive, but the worthlessness of these is more than counterbalanced by the large number whose education is superior to that of the ordinary laborers. |

|

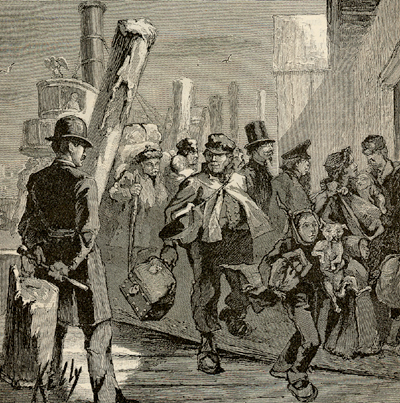

Debarking at Castle Garden |

|

When the baggage has been "passed" by the inspectors, it is checked and sent to a room prepared for its reception. The immigrants are examined by a medical officer who ascertains that no paupers or criminals are among them, and that no persons afflicted with contagious or infectious diseases have escaped the doctor at Quarantine. There is too much ordering about for Giles's liking, but he quickly takes his place. The immigrants are then ushered into the rotunda, a high-roofed circular building, into which ventilations and light are admitted by a dome seventy-five feet high. The floor is divided into small enclosures containing a post-office, telegraph-office, money exchange, and restaurant. As the crowd files in, each passenger is detained for a moment at the registration desk, where his name, age, nationality, destination, the vessels name and the date of arrival are carefully recorded and preserved.

The whole number of immigrants landed at Castle Garden during 1873 was 267,000. The destination of 96,000 was the state of New York, of 44,000 the middle states, of 99,000 the western and north-western states, of 24,000 the eastern states, and of 2,000 the southern states. The whole number arriving in 1874 was 149,584, the destination of 52,444 being the state of New York, 22,630 the middle states, 56,615 the western and north-western states, 12,237 the eastern, 3,506 the southern, and 2,152 Canada. In 1875 the total number of immigrants was 99,093 and in 1876 the total was 113,979.

|

|

A Peep at New York from a Castle Garden Embrasure |

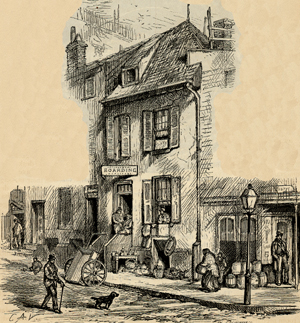

| When the registration is complete a clerk announces the names of the passengers who have friends waiting for the, or for whom letters, telegrams or remittances have been received, and delivery is made to the persons answering. Other passengers who wish to communicate with acquaintances or relatives are referred to clerks who speak and write their language, and their messages are transmitted from the telegraph desk or by mail. The railroad companies have agents in the building, and passengers who wish to leave the city are shown to the ticket offices, while their baggage is recheck and conveyed to the train or depot without charge. Those who want to rest are permitted to remain in the rotunda, where a bowl of coffee, tea or milk and a small loaf of bread are supplied to them for ten cents. If they choose they can go to one of the boarding-houses licensed by the commissioners, which offer food and lodging at the modest price of a dollar or a dollar and a half. But we hope that Giles will not be induced to enter one of these dens. With a few exceptions they are located in an unhealthy neighborhood, frequented by dangerous characters and conducted by reprobate men and women. We pity the immigrant who trusts himself to them. They are defective sanitarily and defective morally, and ought not to be sanctioned by the commissioners. |

|

What is it? |

| During his visit to America, eighteen months age, Joseph Arch expressed his gratification at the care with which immigrants are treated at Castle Garden but regretted that no provision was made for the accommodation of passengers who are detained in the city for a few days. "They are compelled to trust themselves to the licensed boarding houses, which are not, I am assured and can readily believe, very good places for their morals or comfort ****I have an interest, therefore, in suggesting to you the establishment of an Immigrant Home, where cleanliness and comfort would be combined with the protection so freely extended by the commissioners in other manners; this, I would imagine might be rendered self-supporting." |

|

Immigrants' Boarding-House Near the Battery |

|

Attached to Castle Garden ther is also a labor bureau, and if Giles had not an opening in view for himself he might present himself as a candidate. Neither the laborer nor the employer is charged a fee, and the latter is required to prove his responsibility. During 1873 employment was found for 25,400 emigrants, including 14,400 agricultural or common laborers, 3,500 mechanics and 7,000 house servants. In 1874 employment was found for 10,148 men and 6,763 women; in 1875 for 7,008 men and 5,432 women, and in 1876, for 5,394 men, and 4,821 women.

The immigrants are guarded against swindles by a broker's office in the rotunda, where coin is exchanged for bills at the lowest current rates, and where valuables may be deposited without charge. So Giles ought to be grateful, and the vessel-owners ought not to begrudge the small amount of "head money" which secures so many benefits to their best patrons. The last stage of the immigrants' progress is accomplished by rail, and, as far as the vehicle is concerned, it is the least pleasant. An immigrant train is usually made up of dingy old passenger cars, with few windows or means of ventilation. It runs on special time and is managed by conductors of more than ordinary brutality. Each seat has its occupant, ad the atmosphere of the car soon becomes almost suffocation. Smoking is allowed in all the cars, which are filled with fumes of sickening density. At Albany, Rochester, and Buffalo agents of the commissioners examine the passengers and assist them with information; but it is not their business to find fault with the railroad company, and the never do. The long hot, dusty days lapse into long hot and dreary nights. The passengers turn as well as they can in the narrow space of their seats and groan in the vain endeavor to get a wink of refreshing sleep. But after about fifty-six house of misery Giles arrives at this new home, and with his wife and little ones, stands gazing at a broad expanse of untilled land. His work is before him, and it will not be completer until the waste has been cleared and thee earth yielded a tribute to his industry.

|

| If you have any suggestions, corrections, information, copies of documents, or photos that you would like to share with this page, please contact me at maggie@maggieblanck.com | |

| For more information and images of immigration to the United States, particularly New York City go to Immigration | |

| For more information and images of about the immigrant life in New York City go to Tenement Life in New York City | |

| HOME | |

| BLANCK INTRODUCTION | |

| GOEHLE INTRODUCTION | |

| PETERMANN INTRODUCTION | |

| LAND INTRODUCTION | |