| Blizzard, March 12, 1888, New York City |

| HOME |

| More Old Images of New York City |

In March 1888 a hugh blizzard hit the New York area. While I have only been able to find information

on its effect in Manhattan, it can be assumed that Brooklyn and Hoboken, N.J. suffered through

the same storm. The following family was in the area at the time:

| |

|

A struggle to answer a fire-alarm during the New York Blizzard |

|

The "Blizzard" in New York; Twenty-sixth Street on March 12, 1888 |

| The Illustrated London News, collection of Maggie Land Blanck | |

| |

| Aspect of an Up-town Street The Day After The Storm | |

| |

| The Perils of Union Square in The Midst of The Blizzard | |

| |

| Policemen Rubbing Snow on Frozen Ears During the Storm on Monday | |

| |

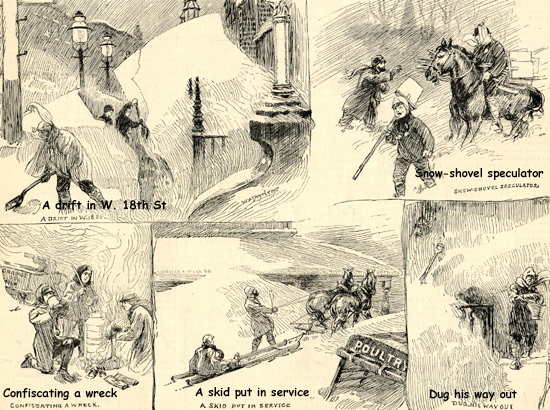

| City Happenings After The Storm. | |

|

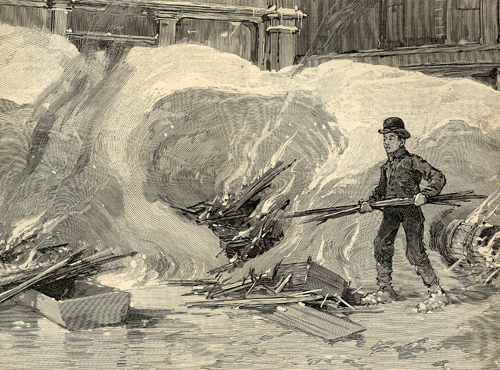

Burning holes in the snow after the storm |

|

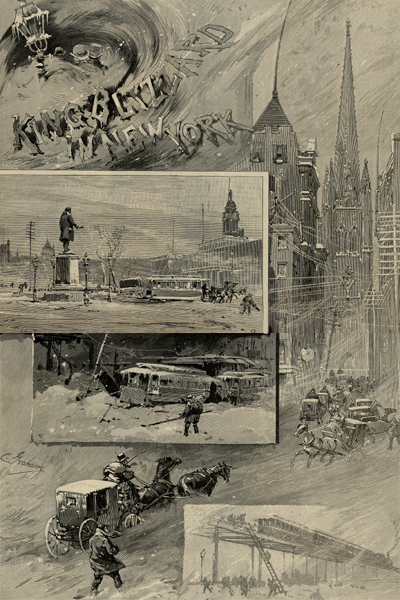

Wall Street in a Fury The City Hall Park Abandoned Street Cars Passengers leaving an Elevated Train by Ladder |

|

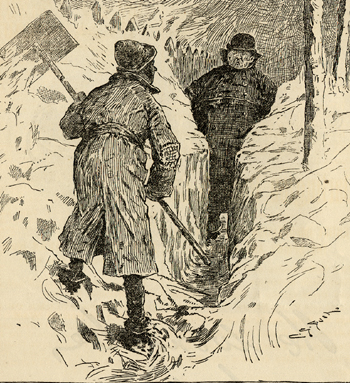

"See here, man, is that the best you can do for a path in front of my house?" "Scuze me, Boss, but the missus told me not ter be to p'tikeler-jes git a path made so's yer might git hum. She's ought ter hev given me yer size. Try it sideways." |

| The following is the complete article about the

blizzard from the March 24, 1888 Harper's Weekly Keep in mind that at the time all of the ancestors listed above lived in cold water flats. The storm which fell upon New York on Monday last was indubitably a blizzard. It was the 12th of March, and the day will be long remembered. Never, so far as people recall or the records show, was the city so tempestuously buffeted before. On Sunday evening there was a heavy rain, which soon after midnight turned into sleet and then in snow. The snow was fine and dry and copious, and was driven by a gale from the west and north. The city had known higher winds and snowfalls as heavy, but never a combination which was so furious. At four o'clock in the morning the snow came so fast that five minutes sufficed to obliterate the footprints of a man or a horse in the streets. Car after car became stalled on the surface roads. At sunrise the city was snowed under. Nine o'clock saw the submission of the elevated roads to the irresistible storm. The switches were clogged by the fine snow, which was blown into the minutest crevices, and the tracks were overspread with ice. In the early morning there had been a collision on the Third Avenue road, and an engineer had been killed. Those who could open their front door in the morning, without admitting a snowdrift of a very respectable size, poked their heads out for a moment, and in a majority of cases decided to stay home for that day, and let business run itself. The city wore a strange aspect. In such a great thoroughfare as the Bowery there was almost no life and movement saving such as the storm furnished. There was no roar and rattle of trains overhead, no clatter of hoofs and jingle of bells in the street below. The air was strangely darkened, something as it was at the time of an eclipse. Occasionally a vehicle or a man on horseback lumbered through the drifts, but locomotion was chiefly performed on foot. It was difficult to see, difficult to breathe, and difficult to keep the frost out of the ears. There was no going in and out of shops, which had been tightly sealed up by the snow. The drifts were littered with broken shafts and wheels, with barber poles, cigar-store Indians, and other fallen signs. Canvas awnings and signs that still swung snapped and creaked in concert with the whistle and swish of the sixty-mile wind and its icy freight. A stranded horse-car lifted its bulk here and there among the other wreckage, and the Bowery contained further in the way of abandoned vehicles two of Uncle Sam's red mail wagons and a huge truck piled up with eighty frozen carcasses of hogs. The entire city was stricken by an amazing paralysis. At ten in the morning not a dozen of the stores in Fulton Street were open for business. In the offices of the Equitable Insurance Company, of the 205 clerks employed, only 93 reported for duty. No public school was open in the afternoon. Washington Market was deserted. At the Post-office nothing was doing. The postmaster said that the mail for the day was like that of a city of ten thousand people. Of forty-four out-of-town mails due between 8 A.M. and noon only four arrived . The trains bearing the other forty were stalled in drifts somewhere, but nobody knew where, because the telegraph wires all about had been beaten down by the storm. New York was cut off from communication by either rail or wire with Newark, Philadelphia, Washington, New Haven, Boston and generally with places east and south. In the limits of the city the storm had beaten down the wires also. The telephones were silent, and half of the fire-alarms were inoperative. Cab fares leaped into startling figures. Twenty dollars was paid for a conveyance from the Astor House to Madison Square, and forty dollars for a cab from Wall Street to Fifth Avenue Hotel. The hotels ran over. The corridors of the Astor House was changed into sleeping rooms, and four hundred applicants for lodging had been turned away at five o'clock in the afternoon. The Custom-house, and the Clearing-house, the Sub-Treasury, the Stock-Exchange, and all the other exchanges were without business on the day of the blizzard, and were closed by noon. In the Produce Exchange only ninety-five members appeared upon the floor: the average daily attendance is seventeen hundred. The great bridge stood the storm well. Observations made in the course of the storm showed that there was not the slightest vibration in the massive piers. But the blizzard was not without effect upon the bridge travel. Trains were run by means of locomotives, the cable and the machinery of the grip yielding to the tempestuous influences. The promenade was closed at six o'clock in the morning. One man, who got special permission to walk across after this hour, fell benumbed and exhausted on the way, but was promptly rescued by the police, who had been instructed to look out for him. The snow was greater than Locomotives. Three engines undertook to push their way out of the Grand Central station through the drifts. They were driven at full pressure, and one of them was thrown off the rails in the attempt to force a passage, but the snow blocked them utterly. In the City Hall there was no Mayor, and in the courts there were no juries. In the afternoon Grand Street shut up its stores, and the letter-carriers were permitted to go home. On the river and the bay the storm was powerful. It snapped off the flag-staffs of the Staten Island ferry-boats the instant they put out their noses in the morning. No trips were made after dark. Pilots said they had never known such furious wind. They called it ten times worse than fog, which had hitherto been the pilots' most dreaded enemy. In crossing the North River one could not see two hundred feet from the boat, and it required strong nerves indeed to make the passage in anything like and equable frame of mind. The helplessness of the elevated roads was demonstrated in the experience of one train loaded with passengers , which consumed six hours and twenty-five minutes in covering a distance of two blocks. This train failed to make the run from Eighteenth Street to Fourteenth on the Sixth Avenue line. Many of the passengers effected their escape, after hours of waiting, by means of a ladder reared against the elevated structure by private enterprise. It cost fifty cents a head to go down the ladder into the comparative freedom of the blizzard and the drifts. With the coming of the night the storm had not abated. The peril to life was very great. Scores of persons were near perishing of fatigue and cold in the streets of this populous city. Mr ROSCOE CONKLING, an athletic man with trained muscles and a powerful frame, was within an ace of perishing in a drift in Union Square. Shortly after six o'clock in the evening he started from Wall Street to walk up Broadway to the New York Club at Twenty-fifth Street. The electric lights had failed, and the great thoroughfare was in darkness. After a walk of two miles in the face of the storm Mr CONKLING reached Union Square. It was unlighted, and trying to cross it he sank into the snow to his armpits. For twenty minutes he put forth his utmost strength in order to work himself free, and he was at the point of exhaustion when he finally succeeded. It took him three hours to walk the two and one miles from Wall Street to the New York Club. One similar case was attended with a fatal result. MR BARREMORE, a merchant, forty-seven years of age, was found on Tuesday morning dead in a drift at Seventh Avenue and Fifty-third Street. He had died of cold and exhaustion within four blocks of his home. The storm shut up all the theatres. It was the opening night of LUDWIG BARNAY, the German actor, and of BARNUM'S SHOW. At the Academy of Music, where BARNAY was to play, twelve persons were assembled in the body of the house, and the performance was postponed. The performance at BARNUM'S was put through for the benefit of less than one hundred people. Fortunately for the firemen and for the city, there was only one fire of consequence on the day of the blizzard. That occurred in Laight Street, at seven o'clock in the evening. A number of engines were stalled in the effort to reach the scene, but others were more fortunate, and the fire was fought successfully. The Sandy-Hook pilot-boats fared most unfortunately under the blizzard. Nine of these sturdy vessels-one third of all that were in commission- were driven ashore or sunk or abandoned before noon and midnight. But the crews of all were saved. In Brooklyn the blizzard blew off the roofs of five houses, which were occupied by nine families. There were serious hurts in consequence, but no loss of life. Tuesday was the day of the shovel. Great heaps of snow, from six to fifteen feet in height, rose in the gutters. Six-footers on one side walk could not see six-footers on the sidewalk opposite. It looked like miles and miles of white fortifications put up with not better purpose than to protect basement windows of houses that nobody meant to attack. All day long the sky was gray, and discharged a lazy "sugar" snow, which added nothing to the city's burden. There was an eruption of runners. Ice, groceries, coal, meat-everything except milk, of which there was none-were delivered in sleighs. Broadway was full of fine sleighs. In the Bowery there was a great deal of tandem driving and horseback riding, all strictly in the way of business. Milk was the greatest want, though there were few eggs and little coal. Veal was scarce, but beef and mutton were plenty. The elevated roads got under way again, and in the afternoon milk came in from Newark, Paterson, and Jamaica. One hundred and twenty funerals had been postponed. Ther were two fires on this day of the shovel. One, at 2 A.M., was in West Forty-second Street, near the ferry. Chief MCCABE went to it on horseback. One hundred families were turned into the street. The fire was put out after an hour's battle. At an afternoon fire in Allen Street hundreds of citizens lent a hand in pulling engines and hose though the drifts. Thousands of Italian shovellers were clearing the surface-car tracks with comparative rapidity. In the morning an ice-bridge formed over the East River, and several thousand persons crossed on foot between New York and Brooklyn. The floe broke with the turn of the tide, and a tugboat was essential to the rescue of five men who were drifting out to sea on small cakes. Wednesday was bonfire day, and it was the day, as well, that saw the city's deliverance. All over the town fire was brought to play to assist the sun in the disposal of the snow. The idea originated, it is said, with a Vase-Street store-keeper, who dug a hole in a snow heap and started a bon fire in it. Soon there was fie leaping up from snow heaps everywhere, and the gutters and sewers were working valiantly to carry the melted part of the city's burden to sea. Wall Street resumed its functions, milk came to town, Boston was heard from by way of London, trains ran on the Central and the Erie, and the world generally resumed relations with us. The storm had been widespread, extending through western New England, New York State, Pennsylvania, and a long way south. Off Lewes, in Delaware, twenty-six vessels were wrecked, and a dozen lives were lost; there were wrecks and loss of life on the Sound and on Staten Island two men were frozen to death. On Thursday, in the city, the bonfires were continued, and the sun was a splendid and efficacious ally. The Horse-cars broke into Park Row, and the gutters sang merrily. On Friday the cross-town cars were running, and some of the snow heaps were not more than five and a half feet high.

| |

| RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE |

| HOME |

| More Old Images of New York City |