WHERE UNTOLD RICHES LIE.

New York's Great Reservoir Full of the World's Wealth.

MODERN CAVES OF ALADDIN.

A Peep Into the Mile of Warehouses That Line the Water Front of Brooklyn

How They are Filled.

N. Y. Sun.

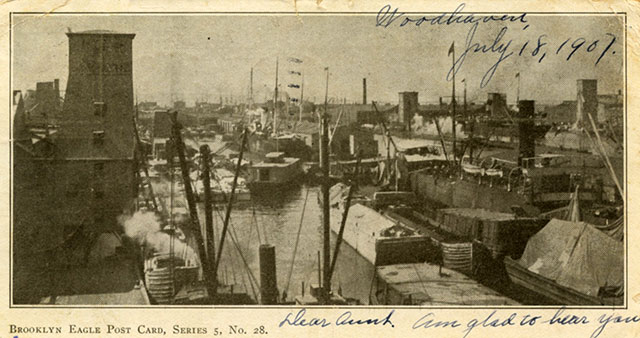

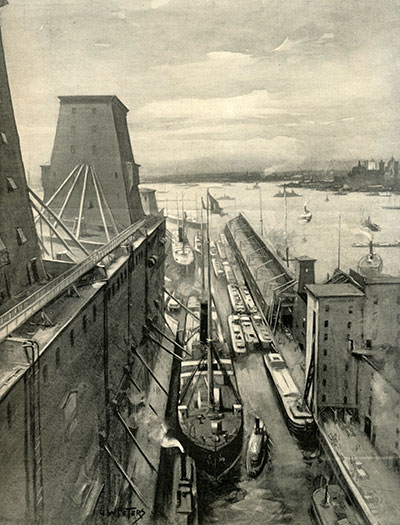

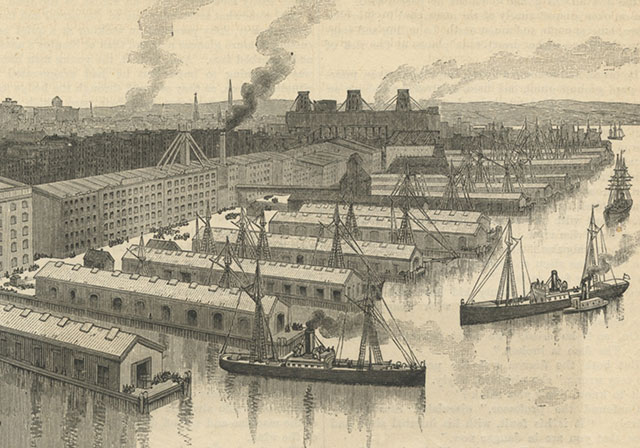

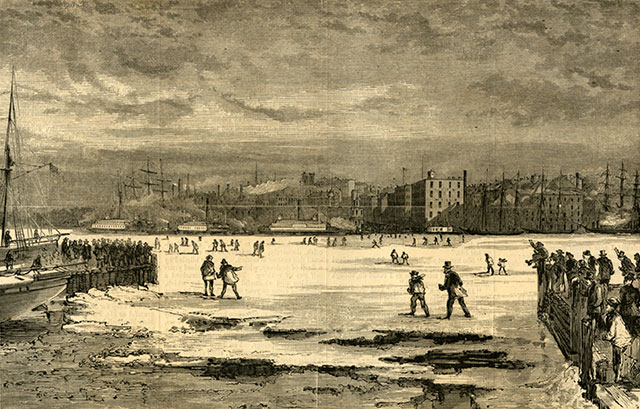

Tho most prominent object that attracts the attention of the passenger

on the Fulton, Wall, or South Ferry is the long line of warehouses that stretches along the

water front of Brooklyn. Back of these warehouses rises the bluff upon which the leaders of

Brooklyn society have built their residences, and to which they have given the name of Brooklyn

Heights. In the mansions luxury reigns. In the storehouses commerce masses all that it

can command to fill the lap of luxury.*

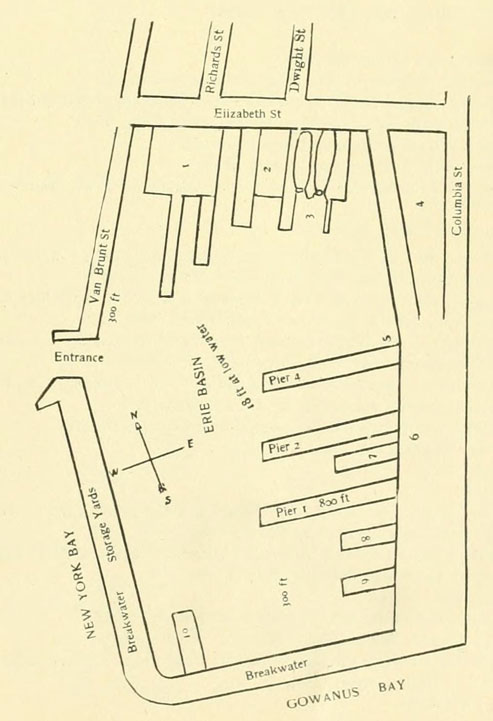

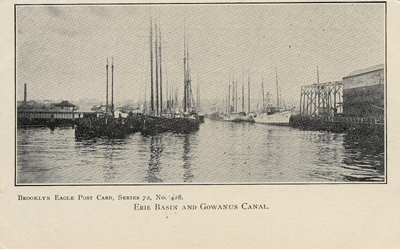

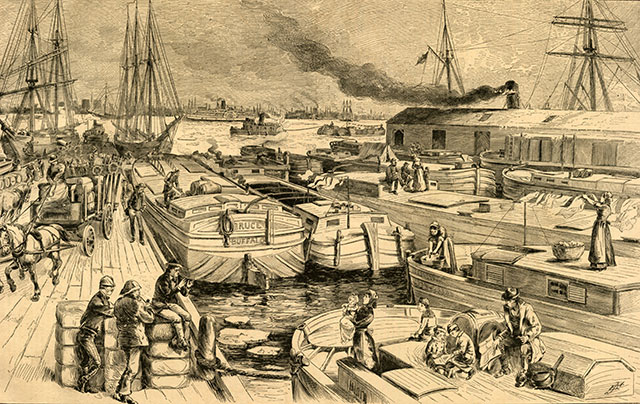

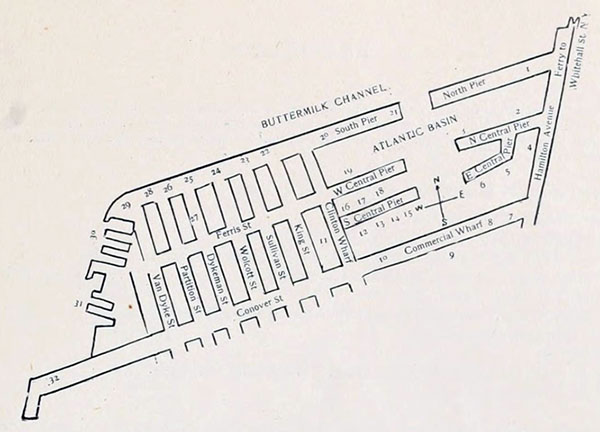

The piers extend out to the channel several hundred feet in front of the storehouses.

These are all brick, and vary from three hundred to live hundred feet in depth.

They stretch in a practically continuous line, broken only by the ferry slips, for

five miles, beginning with the Empire stores, above the great bridge, and extending

beyond the Erie basin.

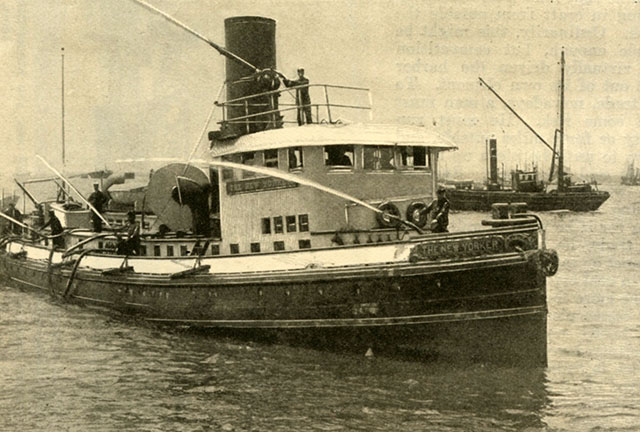

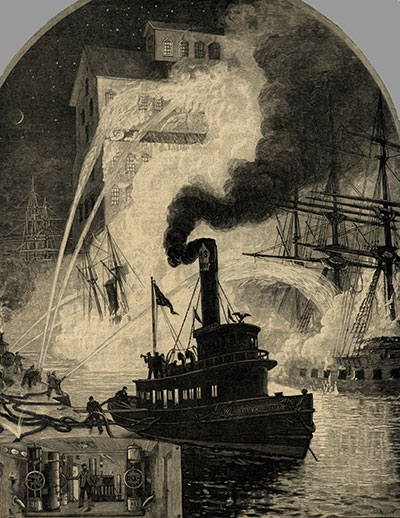

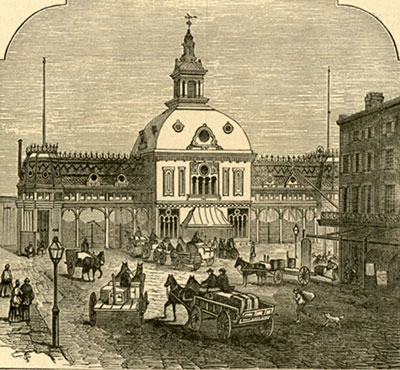

The buildings are not absolutely fireproof, but their walls are so thick that a fire

cannot spread from one to the other. The ceilings are low and the ground floors are dark.

Iron shutters are the rule. There are 7000 feet of them altogether. There is

an appearance of great solidity about the buildings. They were evidently built

to withstand the assaults of time, and to hold secure what is given them to keep.

Not a particle of ornamentation is to be discerned from one end of the long line to the other.

The object for which these buildings were erected is not display, but security.

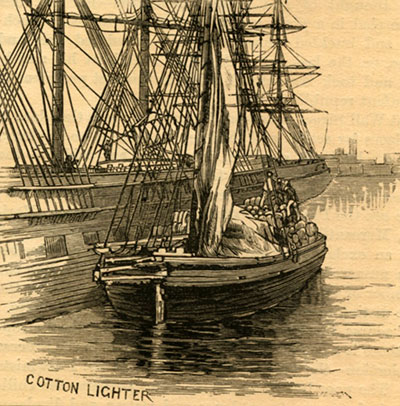

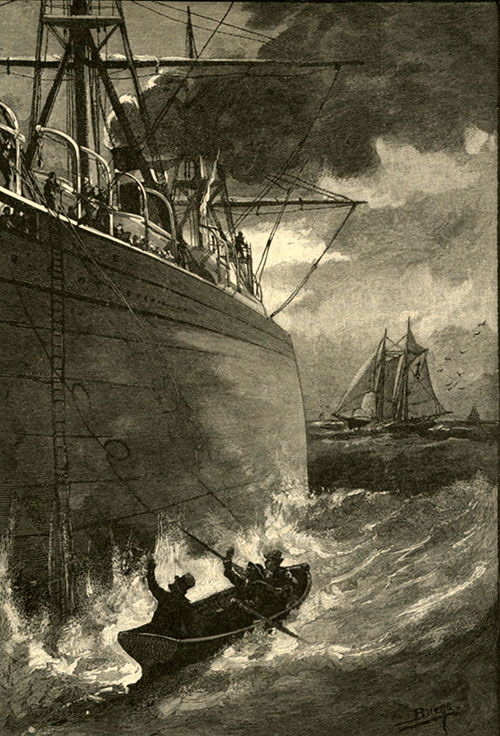

Here are the riches of the metropolis awaiting its order. When the ships of the

merchants come in from foreign shores they unload their freight upon the piers,

and it is rolled back into the deep recesses of the cavernous depths of these

immense warehouses. If the merchant wants money, he takes his warehouse receipts to his

bunk and puts them up as collateral. If he wishes to deliver or ship the goods,

his receipt commands their production on demand, and they come forth, as the

water spouts from the pipe when the faucet is turned, or the light answers to the

touch of an electric button.

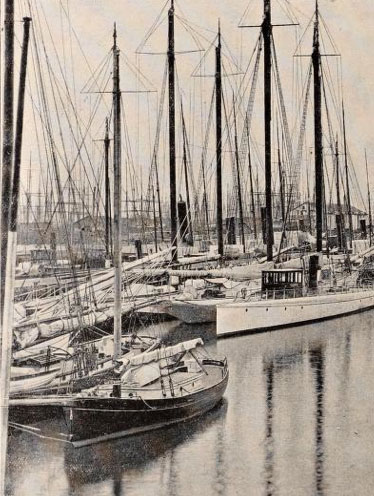

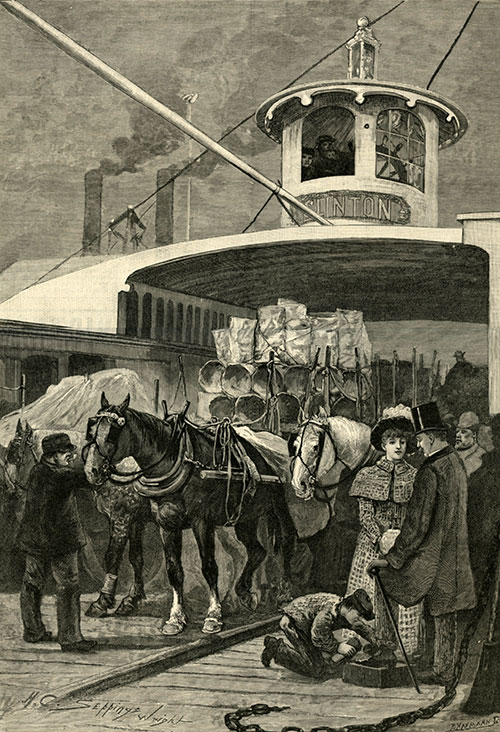

Great archways let in the stout Percherons with huge drays, which cart away hogsheads and crates,

bags and bundles, bales and boxes, in an almost endless procession. As these carry away goods,

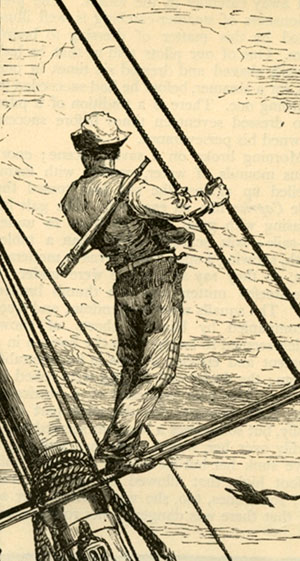

gangs of longshoremen roll on the piers other goods that have been hauled up out of the holds

of sailing vessels and steamships. From the tops of the slender masts float the flags of

nearly all nations, least of all in number being the stars and stripes.

The red flags with cross of St. George is most numerous. The tri-color is prominent,

as is also the red, white and black of Germany. Others are the black, yellow and red of Belgium;

the red, with white cross, of Denmark, the yellow, with red stripes, of Spain; the

blue stripes, with yellow cross and cross in corner, of Sweden; the white, blue and

red stripes of Russia, the yellow, red and blue stripes, with seven white stars on the blue,

of Venezuela; the red, with yellow cross, of Switzerland, and most rare of all,

the white and blue stripes, with white and blue cross, of Greece. The private flags

of the owners display strange devices, some having tigers, lions, crosses, letters and the like.

The piers present a busy scene. An army of custom-house inspectors and weighers in

their white caps calmly survey the scene of which they are indisputably the monarch.

A glance at the labels on their caps enables one to easily distinguish them from the laborers.

The latter are stalwart, with brawny arms, broad chests, bronzed fares and sturdy limbs.

As they trundle the boxes, bales and bags down the pier, they dump them in little

spaces chalked out for different owners. Pools of molasses and a carpet of sugar grains

waste enongh sweetness on the air to tone up the flapjacks and coffee of the whole sixth ward.

The weighers' assistants knock off the boxes from great chunks of what looks like

sawed-off elephants' legs. It is crude rubber that has just arrived from South America,

and has just scraped acquaintance with representatives of the same kind from Australia,

Central America and Africa. The finest comes from Para, in 440 pound boxes.

When cut into looks like canned meat.

As bags of coffee by the hundred are rolled down the piers from the ships, other bags

of pungent aroma slide down with a load swish from the upper stories of the warehouses,

through a long, steeply-inclined chute of canvas. This is so strong and coarse

and the descent is so sharp, that a laborer who essays an easy passage finds himself

in need of a new seat to his trousers at the bottom.

The deep-keel ships from Calcutta and Manila bring huge quantities of jute butts, bamboo, hemp

and cutch-like tar, used in breweries. The Mediterranean line brings fruits nnd skins,

the Jamaica ships bananas, the Rio do Janeiro vessels coffee and rubber, cocoa and birds [?].

Odors float about of tamarinds, cinnamon from the East Indies, cloves, allspice, vanilla beans,

bananas, oranges, lemons, codfish, guano, figs, raisins, niace, tea, sugar and chocolate.

Here is cochineal in cartons [?] made of skins, also indigo.

Hogsheads of molasses spread over acres, and sugar in mats, boxes, and hogsheads

fills warehouse after warehouse.

Men besmeared with tar stir up with huge paddles great caldrons of boiling pitch.

A team of horses jogs lightly along with a load piled to a great height. It is cork with

the bark on and looks like saw logs. Another truck follows with bales of codfish,

and another with hides heavily covered with lime. Over a great pile of rock salt

the bowsprit of a ship, rising and falling with the billowy tide, swings its

flapping sail to and fro like the trunk of an elephant. In the warehouse opposite a

black cat meanders over a great pile of sulphur, while a group of longshoremen play penny ante

on the planks.

There is one picture that is very pretty. The importers of oranges and lemons have

arranged their fruit for inspection by buyers. The boxes are piled in tiers

that rise from the floor of the wharf to the top of the warehouse. The covers of the

boxes have been removed and the boxes laid upon their sides. The fruit is wrapped

in pink, purple, white, red and stiiped paper. Circles have been cut out from

the wrappers; so that segments of the oranges and lemons contribute their bright

colors to the great rainbow. It is a sight worth crossing the river to see.

A great ship with bowsprit extending far over the wharf, has a sea serpent for a figurehead.

Another has a dragon, one a female, another a sailor boy. Here is a general, there a goddess,

here a mermaid, there a seahorse. There is an endless variety of strange

devises from strange climes. Champagne is piled up in great square piles of square boxes.

Wine in casks and boxes, brandy in barrels, beer in tierces and barrels, are here in

quantity. Fortunes are stored in the warehouses and scattered about the immense

wharf surface. One hundred and seventy-five thousand tons of sugar are stored in the

warehouses. This is independent of the 20,000 tons that the Havemeyers usually have

piled away in their private storehouses. Tea by the cargo goes into the building.

Half a million bags of coffee are usually on hand, notwithstanding the fact that,

the cargoes of the ships irom Rio Janeiro quite often are transported to their destinations

in different directions without going into the warehouses at all. Goods are stored, sometimes

for a month, sometimes for a year. The stock of cotton is very heavy when the crop comes in.

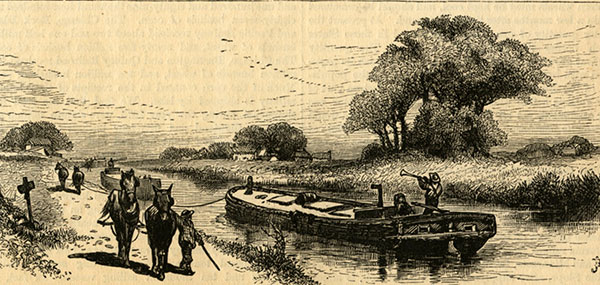

These warehouses were established when the New York merchants stopped storing in the city.

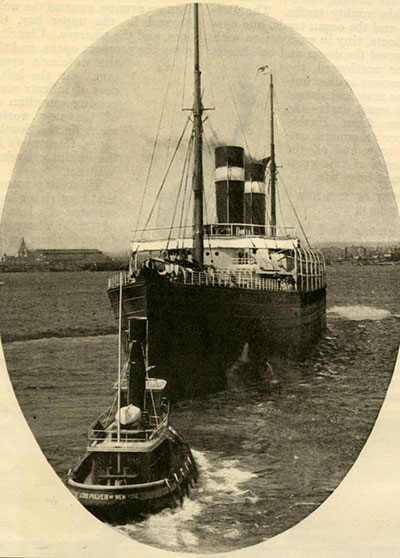

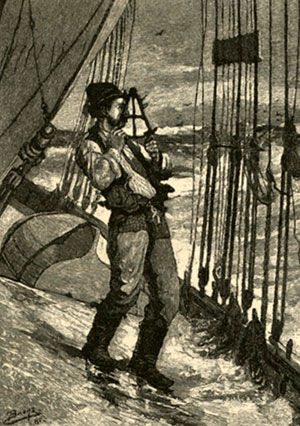

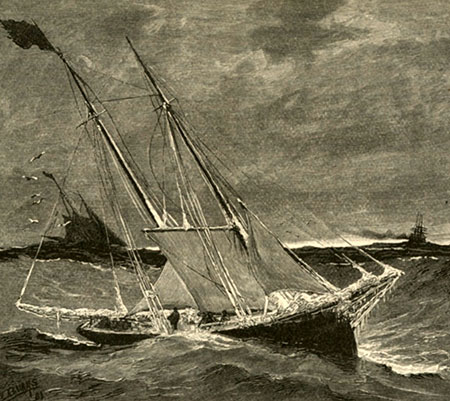

Years ago the clippers, fleet as the wind when upon the sea, rested at these piers, their

fine, lines attracting admiring visitors. The Lord of the Isles, after making her magnificent

day's , record of 4 440 miles, nearly, equaling first-class steamer time,

brought many a cargo to the Atlantic Stores. But nowadays the sailing vessels are the

exceptions.

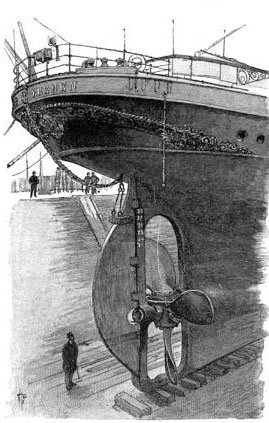

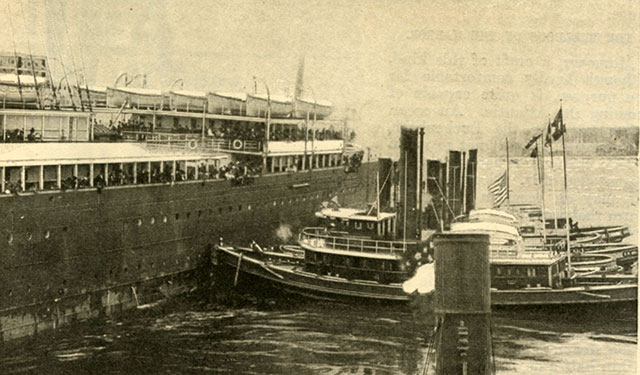

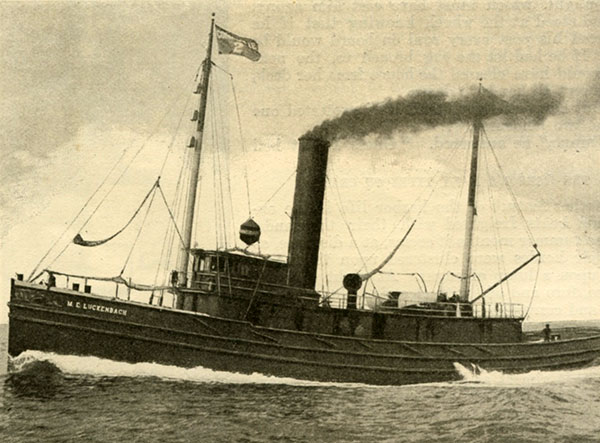

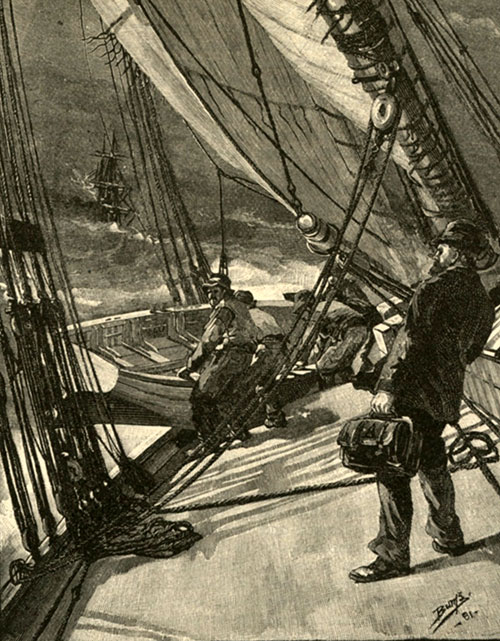

Tramp steamers that skirt the globe, taking in a cargo of furs in Siberia,

selling them in North China, loading with teas in the Flowery Kingdom,

bring their black sides up to the stringpieces, and as chest after chest

goes up out of the hold on the creaking tackle, reveal the deep red of the

lower plates.

Of regular lines of steamship there are the United States mail line to Brazil,

Ward's line to Cuba, Anchor line to Liverpool and the Mediterranean, Red "D"

line to Laguayra, Venezuela, Curacoa, Maracaibo and Pernasibnco.

Booth & Cross' Co's Red Cross line to Brazil, French line to Marseilles,

Alexandra Havana and Mexico. Lambert & Holt line to Rio Janeiro.

There are regular sailing vessel lines to the East Indies that bring cinnamon and spices,

others to Central America, Madagascar, Mozambique and Africa that bring rubber,

and some that bring in casks from Egypt.

If all the rock salt dumped on the piers were piled up in one great heap the cattle of a

thousand hills might lick it for many a month. Sailors of all nationalities toil at the lifts,

mend the sails or stroll about the docks and through the streets in search of adventures.

If they desire a delicate tidbit as a relief from the salt horse or their long sea voyage,

they stroll into the "Crumb," where hash above suspicion may be had for eight cents a plate,

fried liver in laid down at ten cents, and toothsome cruller for the nominal sum of one penny.

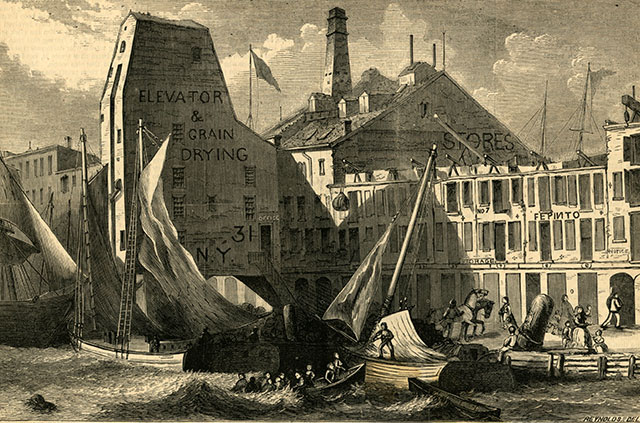

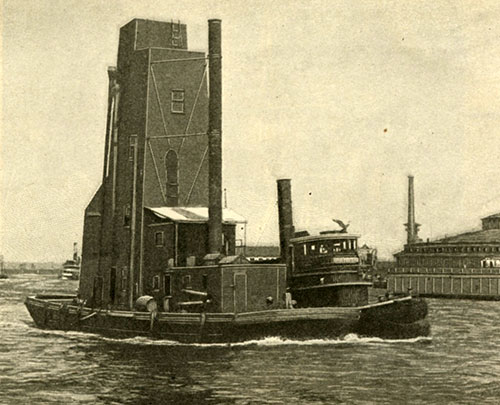

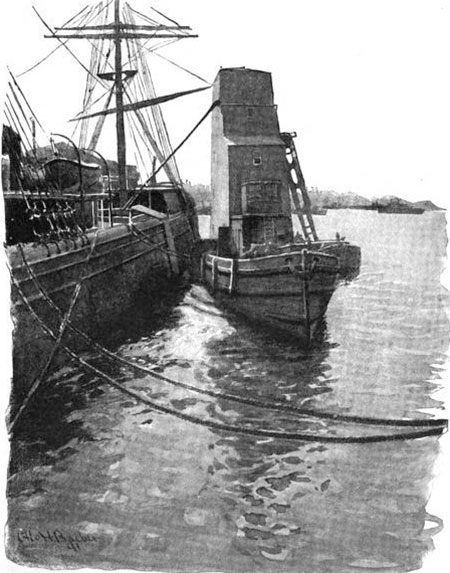

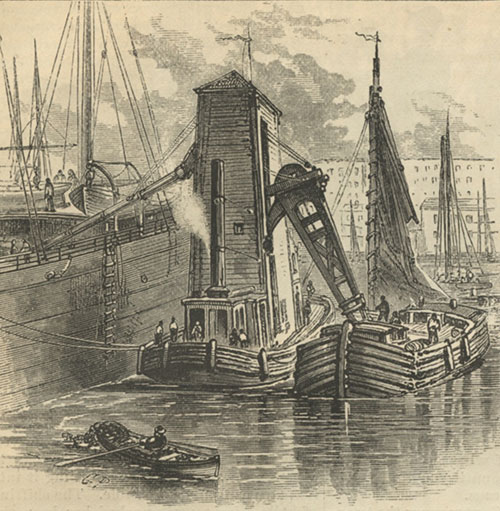

As they lunch they can watch the circling flight of Pinto's pigeons, which grow

fat off the grains of wheat dropped by the long arms of Dow's elevators,

where spouts thrust their greedy lips into the holds of canal boats, and each

gulp 8000 bushels a day, pouring it into the depths of waiting ships.

The tobacco storehouses take in from 15,000 to 25,000 hogsheads of tobacco,

which comes from Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, New York, Illinois and Missouri.

E. B. Bartlett & Co., 19 Old slip, own the Watson, Harbeck, Roberts, Mediterranean,

Baltic, Kelsey, Union, Anglo-American stores, Commercial wharf, and Central and Union elevators.

The United States Warehouse company handles grain. Ward's warehouse specialty is pork.

Martin and Fay handle more coffee and hides than anything else. The Columbia or Dow

stores attend to grain. In the Prentice and Pierrepont store sugar is the feature.

There is over 5,000,000 square foot of storage capacity in these warehouses.

How great the value ot the goods they hold we cannot be told. No records are

kept at any central point, and the goods are coming and going all the while.

But it is safe to say the value is up in the hundreds of millions.

The value of the real estate will round up into nine figures also. Among others

stores are the Pinto, Finlay, Stranahan, German American, Merchants'

(owned by Bartlett, Brookman & C 0.) Beard, Empire, Hamilton, India Wharf, Waverly.

The India Wharf stores are nine and eleven stories high. They were originally a sugar house.

*This describes the waterfront to the north of Red Hook.

Atlantic Basin in 2013, google map

Atlantic Basin in 2013, google map